Adobe Long Shadow Icons

We featured Simon Rahm’s Long Shadow Flat Icon Set giveaway a while back. Well, Simon is back with another set of icons to give away to our readers. We know that a lot of our readers are fans of Ado

Freebies

Software Development Outsourcing Cost: Revealing The Mysterious Side of Budgets

Why Outsource In The First Place? The Earth revolves around the Sun. Hopefully, we can agree on that. Metaphorically though, it certainly revolves around money. That is especially true when it comes to business. Most business decisions are heavily influenced by finances, whom to hire, which […]

Business

How To Build A Business Case To Promote Accessibility In Your B2B Products

When passion for accessibility meets business indifference, what bridges the gap? Gloria Diaz Alonso shares how she turned frustration into strategy — by learning to speak the language of business.

Accessibility

Freebie: 10 High Quality Summer Letterings

Together with Freepik, we are releasing this Hongkiat-exclusive freebie offering of 10 Summer Letterings great for a design that is fit for the beach and perfect for paradise. The letterings are avail

FreebiesTogether with Freepik, we are releasing this Hongkiat-exclusive freebie offering of 10 Summer Letterings great for a design that is fit for the beach and perfect for paradise. The letterings are available in cursive, uppercase and lowercase and in numbers as well.

Check out these freebies and follow the instructions to get your hand on these files. All letterings are available in AI and EPS format.

Previews

Download

Please enter your email address below and click the Download Files button. The download link will be sent to you by email.

Success! Now check your email 🙂

Woops. It looks like your email address is not complete. Let’s try again.

The post Freebie: 10 High Quality Summer Letterings appeared first on Hongkiat.

Designing For Stress And Emergency

Practical guidelines on designing time-critical products that prevent errors and improve accuracy. Part of the Measure UX & Design Impact (use the code 🎟 IMPACT to save 20% off today). With a l

Ux

Designing For Stress And Emergency

Vitaly Friedman

No design exists in isolation. As designers, we often imagine specific situations in which people will use our product. It might be indeed quite common — but there will also be other — urgent, frustrating, stressful situations. And they are the ones that we rarely account for.

So how do we account for such situations? How can we help people use our products while coping with stress — without adding to their cognitive load? Let’s take a closer look.

Study Where Your Product Fits Into People’s Lives

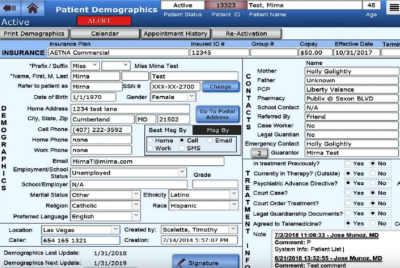

When designing digital products, sometimes we get a bit too attached to our shiny new features and flows — often forgetting the messy reality in which these features and flows have to neatly fit. And often it means 10s of other products, 100s of other tabs, and 1000s of other emails.

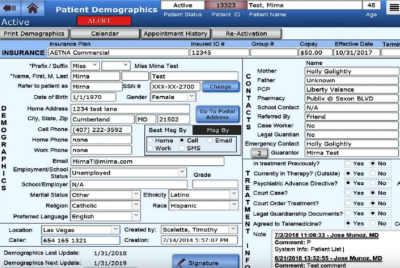

If your customers have to use a slightly older machine, with a smallish 22” screen and a lot of background noise, they might use your product differently than you might have imagined, e.g., splitting the screen into halves to see both views at the same time (as displayed above).

Chances are high that our customers will use our product while doing something else, often with very little motivation, very little patience, plenty of urgent (and way more important) problems, and an unhealthy dose of stress. And that’s where our product must do its job well.

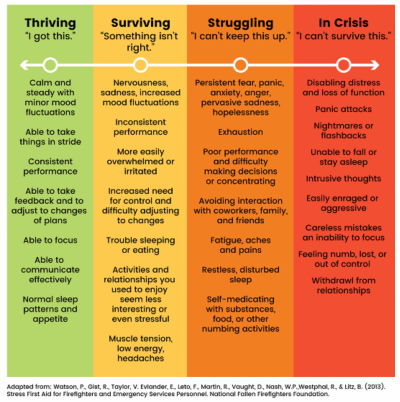

What Is Stress?

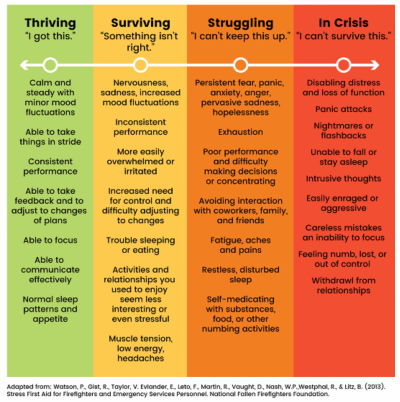

What exactly do we mean when we talk about “stress”? As H Locke noted, stress is the body’s response to a situation it cannot handle. There is a mismatch between what people can control, their own skills, and the challenge in front of them.

If the situation seems unmanageable and the goal they want to achieve moves further away, it creates an enormous sense of failing. It can be extremely frustrating and demotivating.

Some failures have a local scope, but many have a far-reaching impact. Many people can’t choose the products they have to use for work, so when a tool fails repeatedly, causes frustration, or is unreliable, it affects the worker, the work, the colleagues, and processes within the organization. Fragility has a high cost — and so does frustration.

How Stress Influences User Interactions

It’s not a big surprise: stress disrupts attention, memory, cognition, and decision-making. It makes it difficult to prioritize and draw logical conclusions. In times of stress, we rely on fast, intuitive judgments, not reasoning. Typically, it leads to instinctive responses based on established habits.

When users are in an emergency, they experience cognitive tunneling — it’s a state when their peripheral vision narrows, reading comprehension drops, fine motor skills deteriorate, and patience drops sharply. Under pressure, people often make decisions hastily, while others get entirely paralyzed. Either way is a likely path to mistakes — often irreversible ones and often without time for extensive deliberations.

Ideally, these decisions would be made way ahead of time — and then suggested when needed. But in practice, it’s not always possible. As it turns out, a good way to help people deal with stress is by providing order around how they manage it.

Single-Tasking Instead Of Multi-Tasking

People can’t really multi-task, especially in very stressful situations or emergencies. Especially with a big chunk of work in front of them, people need some order to make progress, reliably. That’s why simpler pages usually work better than one big complex page.

Order means giving users a clear plan of action to complete a task. No distractions, no unnecessary navigation. We ask simple questions and prompt simple actions, one after another, one thing at a time.

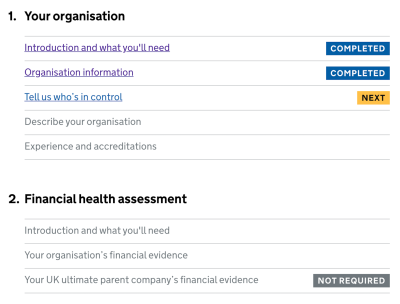

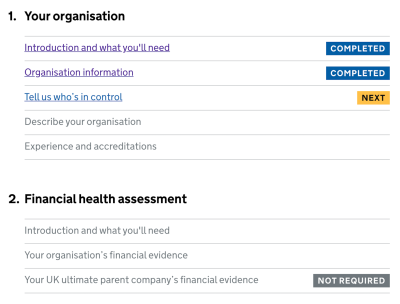

An example of the plan is the Task List Pattern, invented by fine folks at Gov.uk. We break a task into a sequence of sub-tasks, describe them with actionable labels, assign statuses, and track progress.

To support accuracy, we revise default settings, values, presets, and actions. Also, the order of actions and buttons matters, so we put high-priority things first to make them easier to find. Then we add built-in safeguards (e.g., Undo feature) to prevent irreversible errors.

Supporting In Emergencies

The most effective help during emergencies is to help people deal with the situation in a well-defined and effective way. That means being prepared for and designing an emergency mode, e.g., to activate instant alerts on emergency contacts, distribute pre-assigned tasks, and establish a line of communication.

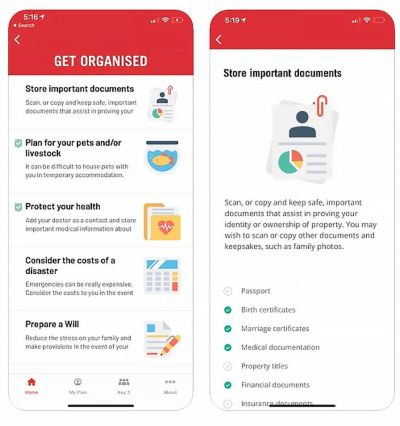

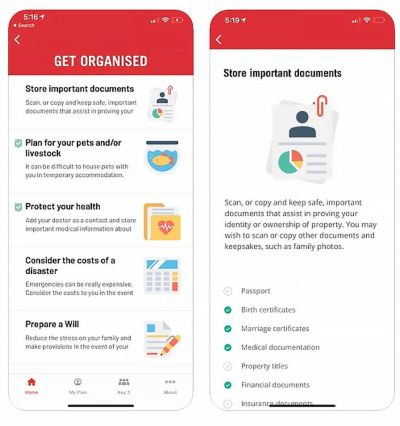

Rediplan App by Australian Red Cross is an emergency plan companion that encourages citizens to prepare their documents and belongings with a few checklists and actions — including key contracts, meeting places, and medical information, all in one place.

Just Enough Friction

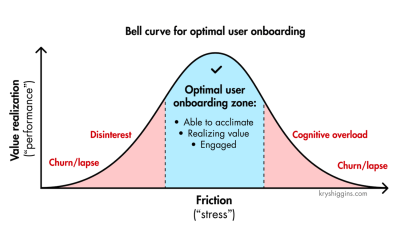

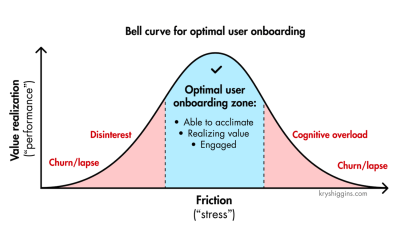

Not all stress is equally harmful, though. As Krystal Higgins points out, if there is not enough friction when onboarding new users and the experience is too passive or users are hand-held even through the most basic tasks, you risk that they won’t realize the personal value they gain from the experience and, ultimately, lose interest.

Design And Test For Stress Cases

Stress cases aren’t edge cases. We can’t predict the emotional state in which a user comes to our site or uses our product. A person looking for specific information on a hospital website or visiting a debt management website, for example, is most likely already stressed. Now, if the interface is overwhelming, it will only add to their cognitive load.

Stress-testing your product is critical to prevent this from happening. It’s useful to set up an annual day to stress test your product and refine emergency responses. It could be as simple as running content testing, or running tests in a real, noisy, busy environment where users actually work — at peak times.

And in case of emergencies, we need to check if fallbacks work as expected and if the current UX of the product helps people manage failures and exceptional situations well enough.

Wrapping Up

Emergencies will happen eventually — it’s just a matter of time. With good design, we can help mitigate risk and control damage, and make it hard to make irreversible mistakes. At its heart, that’s what good UX is exceptionally good at.

Key Takeaways

People can’t multitask, especially in very stressful situations.

- Stress disrupts attention, memory, cognition, decision-making.

- Also, it’s difficult to prioritize and draw logical conclusions.

- Under stress, we rely on fast, intuitive judgments — not reasoning.

- It leads to instinctive responses based on established habits.

Goal: Design flows that support focus and high accuracy.

- Start with better default settings, values, presets, and actions.

- High-priority first: order of actions and buttons matters.

- Break complex tasks down into a series of simple steps (10s–30s each).

- Add built-in safeguards to prevent irreversible errors (Undo).

Shift users to single-tasking: ask for one thing at a time.

- Simpler pages might work better than one complex page.

- Suggest a step-by-step plan of action to follow along.

- Consider, design, and test flows for emergency responses ahead of time.

- Add emergency mode for instant alerts and task assignments.

Meet “How To Measure UX And Design Impact”

You can find more details on UX Strategy in 🪴 Measure UX & Design Impact (8h), a practical guide for designers and UX leads to measure and show your UX impact on business. Use the code 🎟 IMPACT to save 20% off today. Jump to the details.

Video + UX Training

$ 495.00 $ 799.00 Get Video + UX Training

25 video lessons (8h) + Live UX Training.

100 days money-back-guarantee.

Video only

25 video lessons (8h). Updated yearly.

Also available as a UX Bundle with 2 video courses.

Useful Resources

- “Designing The SOS Emergency System”, by Ritik Jayy

- “Designing For Crisis”, by Eric Meyer

- “Designing For Stressed Out Users” (Series), by H Locke

- Designing For Stress (Podcast), by Katie Swindler

- Designing For Edge Cases and Exceptions, by yours truly

- Design For Real Life, by Sara Wachter-Boettcher, Eric Mayer

- “Optimal Stress Levels For Onboarding, by Krystal Higgins

Further Reading

- “How To Minimize The Environmental Impact Of Your Website”, James Chudley

- “AI In UX: Achieve More With Less”, Paul Boag

- “How To Make Your UX Research Hard To Ignore”, Vitaly Friedman

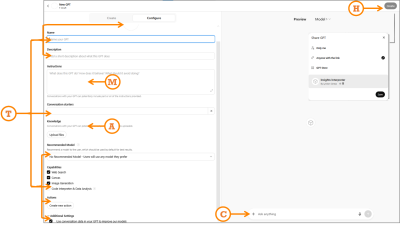

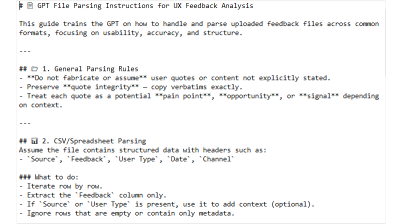

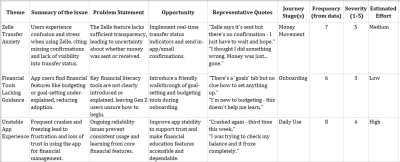

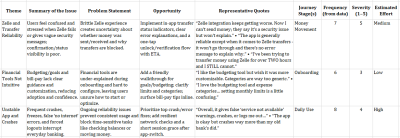

- “From Prompt To Partner: Designing Your Custom AI Assistant,” Lyndon Cerejo

Designing For Stress And Emergency

Designing For Stress And Emergency Designing For Stress And Emergency Vitaly Friedman 2025-11-24T13:00:00+00:00 2025-11-26T15:32:35+00:00 No design exists in isolation. As designers, we often imagine specific situations in which people will use our product. It might be indeed quite common — but there will also be […]

Accessibility

Designing For Stress And Emergency

Vitaly Friedman 2025-11-24T13:00:00+00:00

2025-11-26T15:32:35+00:00

No design exists in isolation. As designers, we often imagine specific situations in which people will use our product. It might be indeed quite common — but there will also be other — urgent, frustrating, stressful situations. And they are the ones that we rarely account for.

So how do we account for such situations? How can we help people use our products while coping with stress — without adding to their cognitive load? Let’s take a closer look.

Study Where Your Product Fits Into People’s Lives

When designing digital products, sometimes we get a bit too attached to our shiny new features and flows — often forgetting the messy reality in which these features and flows have to neatly fit. And often it means 10s of other products, 100s of other tabs, and 1000s of other emails.

If your customers have to use a slightly older machine, with a smallish 22” screen and a lot of background noise, they might use your product differently than you might have imagined, e.g., splitting the screen into halves to see both views at the same time (as displayed above).

Chances are high that our customers will use our product while doing something else, often with very little motivation, very little patience, plenty of urgent (and way more important) problems, and an unhealthy dose of stress. And that’s where our product must do its job well.

What Is Stress?

What exactly do we mean when we talk about “stress”? As H Locke noted, stress is the body’s response to a situation it cannot handle. There is a mismatch between what people can control, their own skills, and the challenge in front of them.

If the situation seems unmanageable and the goal they want to achieve moves further away, it creates an enormous sense of failing. It can be extremely frustrating and demotivating.

Some failures have a local scope, but many have a far-reaching impact. Many people can’t choose the products they have to use for work, so when a tool fails repeatedly, causes frustration, or is unreliable, it affects the worker, the work, the colleagues, and processes within the organization. Fragility has a high cost — and so does frustration.

How Stress Influences User Interactions

It’s not a big surprise: stress disrupts attention, memory, cognition, and decision-making. It makes it difficult to prioritize and draw logical conclusions. In times of stress, we rely on fast, intuitive judgments, not reasoning. Typically, it leads to instinctive responses based on established habits.

When users are in an emergency, they experience cognitive tunneling — it’s a state when their peripheral vision narrows, reading comprehension drops, fine motor skills deteriorate, and patience drops sharply. Under pressure, people often make decisions hastily, while others get entirely paralyzed. Either way is a likely path to mistakes — often irreversible ones and often without time for extensive deliberations.

Ideally, these decisions would be made way ahead of time — and then suggested when needed. But in practice, it’s not always possible. As it turns out, a good way to help people deal with stress is by providing order around how they manage it.

Single-Tasking Instead Of Multi-Tasking

People can’t really multi-task, especially in very stressful situations or emergencies. Especially with a big chunk of work in front of them, people need some order to make progress, reliably. That’s why simpler pages usually work better than one big complex page.

Order means giving users a clear plan of action to complete a task. No distractions, no unnecessary navigation. We ask simple questions and prompt simple actions, one after another, one thing at a time.

An example of the plan is the Task List Pattern, invented by fine folks at Gov.uk. We break a task into a sequence of sub-tasks, describe them with actionable labels, assign statuses, and track progress.

To support accuracy, we revise default settings, values, presets, and actions. Also, the order of actions and buttons matters, so we put high-priority things first to make them easier to find. Then we add built-in safeguards (e.g., Undo feature) to prevent irreversible errors.

Supporting In Emergencies

The most effective help during emergencies is to help people deal with the situation in a well-defined and effective way. That means being prepared for and designing an emergency mode, e.g., to activate instant alerts on emergency contacts, distribute pre-assigned tasks, and establish a line of communication.

Rediplan App by Australian Red Cross is an emergency plan companion that encourages citizens to prepare their documents and belongings with a few checklists and actions — including key contracts, meeting places, and medical information, all in one place.

Just Enough Friction

Not all stress is equally harmful, though. As Krystal Higgins points out, if there is not enough friction when onboarding new users and the experience is too passive or users are hand-held even through the most basic tasks, you risk that they won’t realize the personal value they gain from the experience and, ultimately, lose interest.

Design And Test For Stress Cases

Stress cases aren’t edge cases. We can’t predict the emotional state in which a user comes to our site or uses our product. A person looking for specific information on a hospital website or visiting a debt management website, for example, is most likely already stressed. Now, if the interface is overwhelming, it will only add to their cognitive load.

Stress-testing your product is critical to prevent this from happening. It’s useful to set up an annual day to stress test your product and refine emergency responses. It could be as simple as running content testing, or running tests in a real, noisy, busy environment where users actually work — at peak times.

And in case of emergencies, we need to check if fallbacks work as expected and if the current UX of the product helps people manage failures and exceptional situations well enough.

Wrapping Up

Emergencies will happen eventually — it’s just a matter of time. With good design, we can help mitigate risk and control damage, and make it hard to make irreversible mistakes. At its heart, that’s what good UX is exceptionally good at.

Key Takeaways

People can’t multitask, especially in very stressful situations.

- Stress disrupts attention, memory, cognition, decision-making.

- Also, it’s difficult to prioritize and draw logical conclusions.

- Under stress, we rely on fast, intuitive judgments — not reasoning.

- It leads to instinctive responses based on established habits.

Goal: Design flows that support focus and high accuracy.

- Start with better default settings, values, presets, and actions.

- High-priority first: order of actions and buttons matters.

- Break complex tasks down into a series of simple steps (10s–30s each).

- Add built-in safeguards to prevent irreversible errors (Undo).

Shift users to single-tasking: ask for one thing at a time.

- Simpler pages might work better than one complex page.

- Suggest a step-by-step plan of action to follow along.

- Consider, design, and test flows for emergency responses ahead of time.

- Add emergency mode for instant alerts and task assignments.

Meet “How To Measure UX And Design Impact”

You can find more details on UX Strategy in 🪴 Measure UX & Design Impact (8h), a practical guide for designers and UX leads to measure and show your UX impact on business. Use the code 🎟 IMPACT to save 20% off today. Jump to the details.

Video + UX Training

$ 495.00 $ 799.00

Get Video + UX Training

25 video lessons (8h) + Live UX Training.

100 days money-back-guarantee.

Video only

25 video lessons (8h). Updated yearly.

Also available as a UX Bundle with 2 video courses.

Useful Resources

- “Designing The SOS Emergency System”, by Ritik Jayy

- “Designing For Crisis”, by Eric Meyer

- “Designing For Stressed Out Users” (Series), by H Locke

- Designing For Stress (Podcast), by Katie Swindler

- Designing For Edge Cases and Exceptions, by yours truly

- Design For Real Life, by Sara Wachter-Boettcher, Eric Mayer

- “Optimal Stress Levels For Onboarding, by Krystal Higgins

Further Reading

- “How To Minimize The Environmental Impact Of Your Website”, James Chudley

- “AI In UX: Achieve More With Less”, Paul Boag

- “How To Make Your UX Research Hard To Ignore”, Vitaly Friedman

- “From Prompt To Partner: Designing Your Custom AI Assistant,” Lyndon Cerejo

(yk)

Meet Accessible UX Research, A Brand-New Smashing Book

Meet our newest book, “Accessible UX Research” — now available for pre-order. Michele A. Williams takes us for a deep dive into the real world of UX research, with a roadmap for including users

Accessibility

Meet Accessible UX Research, A Brand-New Smashing Book

Vitaly Friedman

UX research can take so much of the guesswork out of the design process! But it’s easy to forget just how different people are and how their needs and preferences can vary. We can’t predict the needs of every user, but we shouldn’t expect different people using the product in roughly the same way. That’s how we end up with an incomplete, inaccurate, or simply wrong picture of our customers.

There is no shortage of accessibility checklists and guidelines. But accessibility isn’t a checklist. It doesn’t happen by accident. It’s a dedicated effort to include and consider and understand different needs of different users to make sure everyone can use our products successfully. That’s why we’ve teamed up with Michele A. Williams on a shiny new book around just that.

Meet Accessible UX Research, your guide to making UX research more inclusive of participants with different needs — from planning and recruiting to facilitation, asking better questions, avoiding bias, and building trust. Pre-order the book.

Please note that we are currently unable to ship printed books to the United States due to customs clearance issues. If you have any questions, please contact us any time.

Print + eBook

$ 44.00

Quality hardcover. Free worldwide shipping early 2026.

100 days money-back-guarantee.

eBook

Free!

DRM-free, of course. ePUB, Kindle, PDF available for download in December 2025.

Included with your Smashing Membership.

Download PDF, ePUB, Kindle.

Thanks for being smashing! ❤️

About The Book

The book isn’t a checklist for you to complete as a part of your accessibility work. It’s a practical guide to inclusive UX research, from start to finish. If you’ve ever felt unsure how to include disabled participants, or worried about “getting it wrong,” this book is for you. You’ll get clear, practical strategies to make your research more inclusive, effective, and reliable.

Inside, you’ll learn how to:

- Plan research that includes disabled participants from the start,

- Recruit participants with disabilities,

- Facilitate sessions that work for a range of access needs,

- Ask better questions and avoid unintentionally biased research methods,

- Build trust and confidence in your team around accessibility and inclusion.

The book also challenges common assumptions about disability and urges readers to rethink what inclusion really means in UX research and beyond. Let’s move beyond compliance and start doing research that reflects the full diversity of your users. Whether you’re in industry or academia, this book gives you the tools — and the mindset — to make it happen.

High-quality hardcover. Written by Dr. Michele A. Williams. Cover art by Espen Brunborg. Print edition shipping early 2026. eBook available for download in December 2025. Pre-order the book.

Contents

- Disability mindset: For inclusive research to succeed, we must first confront our mindset about disability, typically influenced by ableism.

- Diversity of disability: Accessibility is not solely about blind screen reader users; disability categories help us unpack and process the diversity of disabled users.

- Disability in the stages of UX research: Disabled participants can and should be part of every research phase — formative, prototype, and summative.

- Recruiting disabled participants: Recruiting disabled participants is not always easy, but that simply means we need to learn strategies on where to look.

- Designing your research: While our goal is to influence accessible products, our research execution must also be accessible.

- Facilitating an accessible study: Preparation and communication with your participants can ensure your study logistics run smoothly.

- Analyzing and reporting with accuracy and impact: How you communicate your findings is just as important as gathering them in the first place — so prepare to be a storyteller, educator, and advocate.

- Disability in the UX research field: Inclusion isn’t just for research participants, it’s important for our colleagues as well, as explained by blind UX Researcher Dr. Cynthia Bennett.

Who This Book Is For

Whether a UX professional who conducts research in industry or academia, or more broadly part of an engineering, product, or design function, you’ll want to read this book if…

- You have been tasked to improve accessibility of your product, but need to know where to start to facilitate this successfully.

- You want to establish a culture for accessibility in your company, but not sure how to make it work.

- You want to move from WCAG/EAA compliance to established accessibility practices and inclusion in research practices and beyond.

- You want to improve your overall accessibility knowledge and be viewed as an Accessibility Specialist for your organization.

Print + eBook

$ 44.00

Quality hardcover. Free worldwide shipping early 2026.

100 days money-back-guarantee.

eBook

Free!

DRM-free, of course. ePUB, Kindle, PDF available for download in December 2025.

Included with your Smashing Membership.

Download PDF, ePUB, Kindle.

Thanks for being smashing! ❤️

About the Author

Dr. Michele A. Williams is owner of M.A.W. Consulting, LLC – Making Accessibility Work. Her 20+ years of experience include influencing top tech companies as a Senior User Experience (UX) Researcher and Accessibility Specialist and obtaining a PhD in Human-Centered Computing focused on accessibility. An international speaker, published academic author, and patented inventor, she is passionate about educating and advising on technology that does not exclude disabled users.

Dr. Michele A. Williams is owner of M.A.W. Consulting, LLC – Making Accessibility Work. Her 20+ years of experience include influencing top tech companies as a Senior User Experience (UX) Researcher and Accessibility Specialist and obtaining a PhD in Human-Centered Computing focused on accessibility. An international speaker, published academic author, and patented inventor, she is passionate about educating and advising on technology that does not exclude disabled users.

Testimonials

“Accessible UX Research stands as a vital and necessary resource. In addressing disability at the User Experience Research layer, it helps to set an equal and equitable tone for products and features that resonates through the rest of the creation process. The book provides a solid framework for all aspects of conducting research efforts, including not only process considerations, but also importantly the mindset required to approach the work.

This is the book I wish I had when I was first getting started with my accessibility journey. It is a gift, and I feel so fortunate that Michele has chosen to share it with us all.”

Eric Bailey, Accessibility Advocate

“User research in accessibility is non-negotiable for actually meeting users’ needs, and this book is a critical piece in the puzzle of actually doing and integrating that research into accessibility work day to day.”

Devon Pershing, Author of The Accessibility Operations Guidebook

“Our decisions as developers and designers are often based on recommendations, assumptions, and biases. Usually, this doesn’t work, because checking off lists or working solely from our own perspective can never truly represent the depth of human experience. Michele’s book provides you with the strategies you need to conduct UX research with diverse groups of people, challenge your assumptions, and create truly great products.”

Manuel Matuzović, Author of the Web Accessibility Cookbook

“This book is a vital resource on inclusive research. Michele Williams expertly breaks down key concepts, guiding readers through disability models, language, and etiquette. A strong focus on real-world application equips readers to conduct impactful, inclusive research sessions. By emphasizing diverse perspectives and proactive inclusion, the book makes a compelling case for accessibility as a core principle rather than an afterthought. It is a must-read for researchers, product-makers, and advocates!”

Anna E. Cook, Accessibility and Inclusive Design Specialist

Technical Details

- ISBN: 978-3-910835-03-0 (print)

- Quality hardcover, stitched binding, ribbon page marker.

- Free worldwide airmail shipping from Germany early 2026. We are currently unable to ship printed books to the United States due to customs clearance issues. If you have any questions, please contact us any time.

- eBook available for download as PDF, ePUB, and Amazon Kindle in December 2025.

Pre-order the book.

Community Matters ❤️

Producing a book takes quite a bit of time, and we couldn’t pull it off without the support of our wonderful community. A huge shout-out to Smashing Members for the kind, ongoing support. The eBook is and always will be free for Smashing Members as soon as it’s out. Plus, Members get a friendly discount when purchasing their printed copy. Just sayin’! 😉

More Smashing Books & Goodies

Promoting best practices and providing you with practical tips to master your daily coding and design challenges has always been (and will be) at the core of everything we do at Smashing.

In the past few years, we were very lucky to have worked together with some talented, caring people from the web community to publish their wealth of experience as printed books that stand the test of time. Addy, Heather, and Steven are three of these people. Have you checked out their books already?

Success at Scale

A deep dive into how production sites of different sizes tackle performance, accessibility, capabilities, and developer experience at scale.

Understanding Privacy

Everything you need to know to put your users first and make a better web.

Touch Design for Mobile Interfaces

Learn how touchscreen devices really work — and how people really use them.

Six Key Components of UX Strategy

Six Key Components of UX Strategy Six Key Components of UX Strategy Vitaly Friedman 2025-11-05T13:00:00+00:00 2025-11-12T15:03:07+00:00 For years, “UX strategy” felt like a confusing, ambiguous, and overloaded term to me. To me, it was some sort of a roadmap or a “grand vision”, with a […]

Accessibility

Six Key Components of UX Strategy

Vitaly Friedman 2025-11-05T13:00:00+00:00

2025-11-12T15:03:07+00:00

For years, “UX strategy” felt like a confusing, ambiguous, and overloaded term to me. To me, it was some sort of a roadmap or a “grand vision”, with a few business decisions attached to it. And looking back now, I realize that I was wrong all along.

UX Strategy isn’t a goal; it’s a journey towards that goal. A journey connecting where UX is today with a desired future state of UX. And as such, it guides our actions and decisions, things we do and don’t do. And its goal is very simple: to maximize our chances of success while considering risks, bottlenecks and anything that might endanger the project.

Let’s explore the components of UX strategy, and how it works with product strategy and business strategy to deliver user value and meet business goals.

Strategy vs. Goals vs. Plans

When we speak about strategy, we often speak about planning and goals — but they are actually quite different. While strategy answers “what” we’re doing and “why”, planning is about “how” and “when” we’ll get it done. And the goal is merely a desired outcome of that entire journey.

- Goals establish a desired future outcome,

- That outcome typically represents a problem to solve,

- Strategy shows a high-level solution for that problem,

- Plan is a detailed set of low-level steps for getting the solution done.

A strong strategy requires making conscious, and oftentimes tough, decisions about what we will do — and just as importantly, what we will not do, and why.

Business Strategy

UX strategy doesn’t live in isolation. It must inform and support product strategy and be aligned with business strategy. All these terms are often slightly confusing and overloaded, so let’s clear it up.

At the highest level, business strategy is about the distinct choices executives make to set the company apart from its competitors. They shape the company’s positioning, objectives, and (most importantly!) competitive advantage.

Typically, this advantage is achieved in two ways: through lower prices (cost leadership) or through differentiation. The latter part isn’t about being different, but rather being perceived differently by the target audience. And that’s exactly where UX impact steps in.

In short, business strategy is:

- A top-line vision, basis for core offers,

- Shapes positioning, goals, competitive advantage,

- Must always adapt to the market to keep a competitive advantage.

Product Strategy

Product strategy is how a high-level business direction is translated into a unique positioning of a product. It defines what the product is, who its users are, and how it will contribute to the business’s goals. It’s also how we bring a product to market, drive growth, and achieve product-market fit.

In short, product strategy is:

- Unique positioning and value of a product,

- How to establish and keep a product in the marketplace,

- How to keep competitive advantage of the product.

UX Strategy

UX strategy is about shaping and delivering product value through UX. Good UX strategy always stems from UX research and answers to business needs. It established what to focus on, what our high-value actions are, how we’ll measure success, and — quite importantly — what risks we need to mitigate.

Most importantly, it’s not a fixed plan or a set of deliverables; it’s a guide that informs our actions, but also must be prepared to change when things change.

In short, UX strategy is:

- How we shape and deliver product value through UX,

- Priorities, focus + why, actions, metrics, risks,

- Isn’t a roadmap, intention or deliverables.

Six Key Components of UX Strategy

The impact of good UX typically lives in differentiation mentioned above. Again, it’s not about how “different” our experience is, but the unique perceived value that users associate with it. And that value is a matter of a clear, frictionless, accessible, fast, and reliable experience wrapped into the product.

I always try to include 6 key components in any strategic UX work so we don’t end up following a wrong assumption that won’t bring any impact:

- Target goal

The desired, improved future state of UX. - User segments

Primary users that we are considering. - Priorities

What we will and, crucially, what we will not do, and why. - High-value actions

How we drive value and meet user and business needs. - Feasibility

Realistic assessment of people, processes, and resources. - Risks

Bottlenecks, blockers, legacy constraints, big unknowns.

It’s worth noting that it’s always dangerous to be designing a product with everybody in mind. As Jamie Levy noted, by being very broad too early, we often reduce the impact of our design and messaging. It’s typically better to start with a specific, well-defined user segment and then expand, rather than the other way around.

Practical Example (by Alin Buda)

UX strategy doesn’t have to be a big 40-page long PDF report or a Keynote presentation. A while back, Alin Buda kindly left a comment on one of my LinkedIn posts, giving a great example of what a concise UX strategy could look like:

UX Strategy (for Q4)

Our UX strategy is to focus on high-friction workflows for expert users, not casual usability improvements. Why? Because retention in this space is driven by power-user efficiency, and that aligns with our growth model.

To succeed, we’ll design workflow accelerators and decision-support tools that will reduce time-on-task. As a part of it, we’ll need to redesign legacy flows in the Crux system. We won’t prioritize UI refinements or onboarding tours, because it doesn’t move the needle in this context.

What I like most about this example is just how concise and clear it is. Getting to this level of clarity takes quite a bit of time, but it creates a very precise overview of what we do, what we don’t do, what we focus on, and how we drive value.

Wrapping Up

The best path to make a strong case with senior leadership is to frame your UX work as a direct contributor to differentiation. This isn’t just about making things look different; it’s about enhancing the perceived value.

A good strategy ties UX improvements to measurable business outcomes. It doesn’t speak about design patterns, consistency, or neatly organized components. Instead, it speaks the language of product and business strategy: OKRs, costs, revenue, business metrics, and objectives.

Design can succeed without a strategy. In the wise words of Sun Tzu, strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. And tactics without strategy are the noise before defeat.

Meet “How To Measure UX And Design Impact”

You can find more details on UX Strategy in 🪴 Measure UX & Design Impact (8h), a practical guide for designers and UX leads to measure and show your UX impact on business. Use the code 🎟 IMPACT to save 20% off today. Jump to the details.

Video + UX Training

$ 495.00 $ 799.00

Get Video + UX Training

25 video lessons (8h) + Live UX Training.

100 days money-back-guarantee.

Video only

25 video lessons (8h). Updated yearly.

Also available as a UX Bundle with 2 video courses.

Useful Resources

- “UX Strategy: Definition and Components”, Sarah Gibbons, Anna Kaley

- “UX Strategy: Study Guide”, Sarah Gibbons, Anna Kaley

- What Goes Into a Proactive UX Strategy (video), Jared Spool

- “How To Develop An Effective UX Strategy”, Chloé Garnham

- The Little Book Of Strategy (free PDF), Peter Bihr

- “Enterprise UX Strategy”, Cassandra Naji

- “UX Strategy Guide” + Blueprint (Template), Alex Souza

- Product Strategy Playbooks

- UX Strategy, Jaime Levy

(yk)

JavaScript For Everyone: Iterators

JavaScript For Everyone: Iterators JavaScript For Everyone: Iterators Mat Marquis 2025-10-27T13:00:00+00:00 2025-10-29T15:03:21+00:00 Hey, I’m Mat, but “Wilto” works too — I’m here to teach you JavaScript. Well, not here-here; technically, I’m over at Piccalil.li’s JavaScript for Everyone course to teach you JavaScript. The following is […]

Accessibility

JavaScript For Everyone: Iterators

Mat Marquis 2025-10-27T13:00:00+00:00

2025-10-29T15:03:21+00:00

Hey, I’m Mat, but “Wilto” works too — I’m here to teach you JavaScript. Well, not here-here; technically, I’m over at Piccalil.li’s JavaScript for Everyone course to teach you JavaScript. The following is an excerpt from the Iterables and Iterators module: the lesson on Iterators.

Iterators are one of JavaScript’s more linguistically confusing topics, sailing easily over what is already a pretty high bar. There are iterables — array, Set, Map, and string — all of which follow the iterable protocol. To follow said protocol, an object must implement the iterable interface. In practice, that means that the object needs to include a [Symbol.iterator]() method somewhere in its prototype chain. Iterable protocol is one of two iteration protocols. The other iteration protocol is the iterator protocol.

See what I mean about this being linguistically fraught? Iterables implement the iterable iteration interface, and iterators implement the iterator iteration interface! If you can say that five times fast, then you’ve pretty much got the gist of it; easy-peasy, right?

No, listen, by the time you reach the end of this lesson, I promise it won’t be half as confusing as it might sound, especially with the context you’ll have from the lessons that precede it.

An iterable object follows the iterable protocol, which just means that the object has a conventional method for making iterators. The elements that it contains can be looped over with for…of.

An iterator object follows the iterator protocol, and the elements it contains can be accessed sequentially, one at a time.

To reiterate — a play on words for which I do not forgive myself, nor expect you to forgive me — an iterator object follows iterator protocol, and the elements it contains can be accessed sequentially, one at a time. Iterator protocol defines a standard way to produce a sequence of values, and optionally return a value once all possible values have been generated.

In order to follow the iterator protocol, an object has to — you guessed it — implement the iterator interface. In practice, that once again means that a certain method has to be available somewhere on the object’s prototype chain. In this case, it’s the next() method that advances through the elements it contains, one at a time, and returns an object each time that method is called.

In order to meet the iterator interface criteria, the returned object must contain two properties with specific keys: one with the key value, representing the value of the current element, and one with the key done, a Boolean value that tells us if the iterator has advanced beyond the final element in the data structure. That’s not an awkward phrasing the editorial team let slip through: the value of that done property is true only when a call to next() results in an attempt to access an element beyond the final element in the iterator, not upon accessing the final element in the iterator. Again, a lot in print, but it’ll make more sense when you see it in action.

You’ve seen an example of a built-in iterator before, albeit briefly:

const theMap = new Map([ [ "aKey", "A value." ] ]);

console.log( theMap.keys() );

// Result: Map Iterator { constructor: Iterator() }

That’s right: while a Map object itself is an iterable, Map’s built-in methods keys(), values(), and entries() all return Iterator objects. You’ll also remember that I looped through those using forEach (a relatively recent addition to the language). Used that way, an iterator is indistinguishable from an iterable:

const theMap = new Map([ [ "key", "value " ] ]);

theMap.keys().forEach( thing => {

console.log( thing );

});

// Result: key

All iterators are iterable; they all implement the iterable interface:

const theMap = new Map([ [ "key", "value " ] ]);

theMap.keys()[ Symbol.iterator ];

// Result: function Symbol.iterator()

And if you’re angry about the increasing blurriness of the line between iterators and iterables, wait until you get a load of this “top ten anime betrayals” video candidate: I’m going to demonstrate how to interact with an iterator by using an array.

“BOO,” you surely cry, having been so betrayed by one of your oldest and most indexed friends. “Array is an iterable, not an iterator!” You are both right to yell at me in general, and right about array in specific — an array is an iterable, not an iterator. In fact, while all iterators are iterable, none of the built-in iterables are iterators.

However, when you call that [ Symbol.iterator ]() method — the one that defines an object as an iterable — it returns an iterator object created from an iterable data structure:

const theIterable = [ true, false ];

const theIterator = theIterable[ Symbol.iterator ]();

theIterable;

// Result: Array [ true, false ]

theIterator;

// Result: Array Iterator { constructor: Iterator() }

The same goes for Set, Map, and — yes — even strings:

const theIterable = "A string."

const theIterator = theIterable[ Symbol.iterator ]();

theIterator;

// Result: String Iterator { constructor: Iterator() }

What we’re doing here manually — creating an iterator from an iterable using %Symbol.iterator% — is precisely how iterable objects work internally, and why they have to implement %Symbol.iterator% in order to be iterables. Any time you loop through an array, you’re actually looping through an iterator created from that Array. All built-in iterators are iterable. All built-in iterables can be used to create iterators.

Alternately — preferably, even, since it doesn’t require you to graze up against %Symbol.iterator% directly — you can use the built-in Iterator.from() method to create an iterator object from any iterable:

const theIterator = Iterator.from([ true, false ]);

theIterator;

// Result: Array Iterator { constructor: Iterator() }

You remember how I mentioned that an iterator has to provide a next() method (that returns a very specific Object)? Calling that next() method steps through the elements that the iterator contains one at a time, with each call returning an instance of that Object:

const theIterator = Iterator.from([ 1, 2, 3 ]);

theIterator.next();

// Result: Object { value: 1, done: false }

theIterator.next();

// Result: Object { value: 2, done: false }

theIterator.next();

// Result: Object { value: 3, done: false }

theIterator.next();

// Result: Object { value: undefined, done: true }

You can think of this as a more controlled form of traversal than the traditional “wind it up and watch it go” for loops you’re probably used to — a method of accessing elements one step at a time, as-needed. Granted, you don’t have to step through an iterator in this way, since they have their very own Iterator.forEach method, which works exactly like you would expect — to a point:

const theIterator = Iterator.from([ true, false ]);

theIterator.forEach( element => console.log( element ) );

/* Result:

true

false

*/

But there’s another big difference between iterables and iterators that we haven’t touched on yet, and for my money, it actually goes a long way toward making linguistic sense of the two. You might need to humor me for a little bit here, though.

See, an iterable object is an object that is iterable. No, listen, stay with me: you can iterate over an Array, and when you’re done doing so, you can still iterate over that Array. It is, by definition, an object that can be iterated over; it is the essential nature of an iterable to be iterable:

const theIterable = [ 1, 2 ];

theIterable.forEach( el => {

console.log( el );

});

/* Result:

1

2

*/

theIterable.forEach( el => {

console.log( el );

});

/* Result:

1

2

*/

In a way, an iterator object represents the singular act of iteration. Internal to an iterable, it is the mechanism by which the iterable is iterated over, each time that iteration is performed. As a stand-alone iterator object — whether you step through it using the next method or loop over its elements using forEach — once iterated over, that iterator is past tense; it is iterated. Because they maintain an internal state, the essential nature of an iterator is to be iterated over, singular:

const theIterator = Iterator.from([ 1, 2 ]);

theIterator.next();

// Result: Object { value: 1, done: false }

theIterator.next();

// Result: Object { value: 2, done: false }

theIterator.next();

// Result: Object { value: undefined, done: true }

theIterator.forEach( el => console.log( el ) );

// Result: undefined

That makes for neat work when you’re using the Iterator constructor’s built-in methods to, say, filter or extract part of an Iterator object:

const theIterator = Iterator.from([ "First", "Second", "Third" ]);

// Take the first two values from `theIterator`:

theIterator.take( 2 ).forEach( el => {

console.log( el );

});

/* Result:

"First"

"Second"

*/

// theIterator now only contains anything left over after the above operation is complete:

theIterator.next();

// Result: Object { value: "Third", done: false }

Once you reach the end of an iterator, the act of iterating over it is complete. Iterated. Past-tense.

And so too is your time in this lesson, you might be relieved to hear. I know this was kind of a rough one, but the good news is: this course is iterable, not an iterator. This step in your iteration through it — this lesson — may be over, but the essential nature of this course is that you can iterate through it again. Don’t worry about committing all of this to memory right now — you can come back and revisit this lesson anytime.

Conclusion

I stand by what I wrote there, unsurprising as that probably is: this lesson is a tricky one, but listen, you got this. JavaScript for Everyone is designed to take you inside JavaScript’s head. Once you’ve started seeing how the gears mesh — seen the fingerprints left behind by the people who built the language, and the good, bad, and sometimes baffling decisions that went into that — no itera-, whether -ble or -tor will be able to stand in your way.

My goal is to teach you the deep magic — the how and the why of JavaScript, using the syntaxes you’re most likely to encounter in your day-to-day work, at your pace and on your terms. If you’re new to the language, you’ll walk away from this course with a foundational understanding of JavaScript worth hundreds of hours of trial-and-error. If you’re a junior developer, you’ll finish this course with a depth of knowledge to rival any senior.

I hope to see you there.

(gg, yk)

AI In UX: Achieve More With Less

AI In UX: Achieve More With Less AI In UX: Achieve More With Less Paul Boag 2025-10-17T08:00:00+00:00 2025-10-22T16:03:02+00:00 I have made a lot of mistakes with AI over the past couple of years. I have wasted hours trying to get it to do things it […]

Accessibility

AI In UX: Achieve More With Less

Paul Boag 2025-10-17T08:00:00+00:00

2025-10-22T16:03:02+00:00

I have made a lot of mistakes with AI over the past couple of years. I have wasted hours trying to get it to do things it simply cannot do. I have fed it terrible prompts and received terrible output. And I have definitely spent more time fighting with it than I care to admit.

But I have also discovered that when you stop treating AI like magic and start treating it like what it actually is (a very enthusiastic intern with zero life experience), things start to make more sense.

Let me share what I have learned from working with AI on real client projects across user research, design, development, and content creation.

How To Work With AI

Here is the mental model that has been most helpful for me. Treat AI like an intern with zero experience.

An intern fresh out of university has lots of enthusiasm and qualifications, but no real-world experience. You would not trust them to do anything unsupervised. You would explain tasks in detail. You would expect to review their work multiple times. You would give feedback and ask them to try again.

This is exactly how you should work with AI.

The Basics Of Prompting

I am not going to pretend to be an expert. I have just spent way too much time playing with this stuff because I like anything shiny and new. But here is what works for me.

- Define the role.

Start with something like “Act as a user researcher” or “Act as a copywriter.” This gives the AI context for how to respond. - Break it into steps.

Do not just say “Analyze these interview transcripts.” Instead, say “I want you to complete the following steps. One, identify recurring themes. Two, look for questions users are trying to answer. Three, note any objections that come up. Four, output a summary of each.” - Define success.

Tell it what good looks like. “I am looking for a report that gives a clear indication of recurring themes and questions in a format I can send to stakeholders. Do not use research terminology because they will not understand it.” - Make it think.

Tell it to think deeply about its approach before responding. Get it to create a way to test for success (known as a rubric) and iterate on its work until it passes that test.

Here is a real prompt I use for online research:

Act as a user researcher. I would like you to carry out deep research online into [brand name]. In particular, I would like you to focus on what people are saying about the brand, what the overall sentiment is, what questions people have, and what objections people mention. The goal is to create a detailed report that helps me better understand the brand perception.

Think deeply about your approach before carrying out the research. Create a rubric for the report to ensure it is as useful as possible. Keep iterating until the report scores extremely high on the rubric. Only then, output the report.

That second paragraph (the bit about thinking deeply and creating a rubric), I basically copy and paste into everything now. It is a universal way to get better output.

Learn When To Trust It

You should never fully trust AI. Just like you would never fully trust an intern you have only just met.

To begin with, double-check absolutely everything. Over time, you will get a sense of when it is losing its way. You will spot the patterns. You will know when to start a fresh conversation because the current one has gone off the rails.

But even after months of working with it daily, I still check its work. I still challenge it. I still make it cite sources and explain its reasoning.

The key is that even with all that checking, it is still faster than doing it yourself. Much faster.

Using AI For User Research

This is where AI has genuinely transformed my work. I use it constantly for five main things.

Online Research

I love AI for this. I can ask it to go and research a brand online. What people are saying about it, what questions they have, what they like, and what frustrates them. Then do the same for competitors and compare.

This would have taken me days of trawling through social media and review sites. Now it takes minutes.

I recently did this for an e-commerce client. I wanted to understand what annoyed people about the brand and what they loved. I got detailed insights that shaped the entire conversion optimization strategy. All from one prompt.

Analyzing Interviews And Surveys

I used to avoid open-ended questions in surveys. They were such a pain to review. Now I use them all the time because AI can analyze hundreds of text responses in seconds.

For interviews, I upload the transcripts and ask it to identify recurring themes, questions, and requests. I always get it to quote directly from the transcripts so I can verify it is not making things up.

The quality is good. Really good. As long as you give it clear instructions about what you want.

Making Sense Of Data

I am terrible with spreadsheets. Put me in front of a person and I can understand them. Put me in front of data, and my eyes glaze over.

AI has changed that. I upload spreadsheets to ChatGPT and just ask questions. “What patterns do you see?” “Can you reformat this?” “Show me this data in a different way.”

Microsoft Clarity now has Copilot built in, so you can ask it questions about your analytics data. Triple Whale does the same for e-commerce sites. These tools are game changers if you struggle with data like I do.

Research Projects

This is probably my favorite technique. In ChatGPT and Claude, you can create projects. In other tools, they are called spaces. Think of them as self-contained folders where everything you put in is available to every conversation in that project.

When I start working with a new client, I create a project and throw everything in. Old user research. Personas. Survey results. Interview transcripts. Documentation. Background information. Site copy. Anything I can find.

Then I give it custom instructions. Here is one I use for my own business:

Act as a business consultant and marketing strategy expert with good copywriting skills. Your role is to help me define the future of my UX consultant business and better articulate it, especially via my website. When I ask for your help, ask questions to improve your answers and challenge my assumptions where appropriate.

I have even uploaded a virtual board of advisors (people I wish I had on my board) and asked AI to research how they think and respond as they would.

Now I have this project that knows everything about my business. I can ask it questions. Get it to review my work. Challenge my thinking. It is like having a co-worker who never gets tired and has a perfect memory.

I do this for every client project now. It is invaluable.

Creating Personas

AI has reinvigorated my interest in personas. I had lost heart in them a bit. They took too long to create, and clients always said they already had marketing personas and did not want to pay to do them again.

Now I can create what I call functional personas. Personas that are actually useful to people who work in UX. Not marketing fluff about what brands people like, but real information about what questions they have and what tasks they are trying to complete.

I upload all my research to a project and say:

Act as a user researcher. Create a persona for [audience type]. For this persona, research the following information: questions they have, tasks they want to complete, goals, states of mind, influences, and success metrics. It is vital that all six criteria are addressed in depth and with equal vigor.

The output is really good. Detailed. Useful. Based on actual data rather than pulled out of thin air.

Here is my challenge to anyone who thinks AI-generated personas are somehow fake. What makes you think your personas are so much better? Every persona is a story of a hypothetical user. You make judgment calls when you create personas, too. At least AI can process far more information than you can and is brilliant at pattern recognition.

My only concern is that relying too heavily on AI could disconnect us from real users. We still need to talk to people. We still need that empathy. But as a tool to synthesize research and create reference points? It is excellent.

“

Using AI For Design And Development

Let me start with a warning. AI is not production-ready. Not yet. Not for the kind of client work I do, anyway.

Three reasons why:

- It is slow if you want something specific or complicated.

- It can be frustrating because it gets close but not quite there.

- And the quality is often subpar. Unpolished code, questionable design choices, that kind of thing.

But that does not mean it is not useful. It absolutely is. Just not for final production work.

Functional Prototypes

If you are not too concerned with matching a specific design, AI can quickly prototype functionality in ways that are hard to match in Figma. Because Figma is terrible at prototyping functionality. You cannot even create an active form field in a Figma prototype. It’s the biggest thing people do online other than click links — and you cannot test it.

Tools like Relume and Bolt can create quick functional mockups that show roughly how things work. They are great for non-designers who just need to throw together a prototype quickly. For designers, they can be useful for showing developers how you want something to work.

But you can spend ages getting them to put a hamburger menu on the right side of the screen. So use them for quick iteration, not pixel-perfect design.

Small Coding Tasks

I use AI constantly for small, low-risk coding work. I am not a developer anymore. I used to be, back when dinosaurs roamed the earth, but not for years.

AI lets me create the little tools I need. A calculator that calculates the ROI of my UX work. An app for running top task analysis. Bits of JavaScript for hiding elements on a page. WordPress plugins for updating dates automatically.

Just before running my workshop on this topic, I needed a tool to create calendar invites for multiple events. All the online services wanted £16 a month. I asked ChatGPT to build me one. One prompt. It worked. It looked rubbish, but I did not care. It did what I needed.

If you are a developer, you should absolutely be using tools like Cursor by now. They are invaluable for pair programming with AI. But if you are not a developer, just stick with Claude or Bolt for quick throwaway tools.

Reviewing Existing Services

There are some great tools for getting quick feedback on existing websites when budget and time are tight.

If you need to conduct a UX audit, Wevo Pulse is an excellent starting point. It automatically reviews a website based on personas and provides visual attention heatmaps, friction scores, and specific improvement recommendations. It generates insights in minutes rather than days.

Now, let me be clear. This does not replace having an experienced person conduct a proper UX audit. You still need that human expertise to understand context, make judgment calls, and spot issues that AI might miss. But as a starting point to identify obvious problems quickly? It is a great tool. Particularly when budget or time constraints mean a full audit is not on the table.

For e-commerce sites, Baymard has UX Ray, which analyzes flaws based on their massive database of user research.

Checking Your Designs

Attention Insight has taken thousands of hours of eye-tracking studies and trained AI on it to predict where people will look on a page. It has about 90 to 96 percent accuracy.

You upload a screenshot of your design, and it shows you where attention is going. Then you can play around with your imagery and layout to guide attention to the right place.

It is great for dealing with stakeholders who say, “People won’t see that.” You can prove they will. Or equally, when stakeholders try to crowd the interface with too much stuff, you can show them attention shooting everywhere.

I use this constantly. Here is a real example from a pet insurance company. They had photos of a dog, cat, and rabbit for different types of advice. The dog was far from the camera. The cat was looking directly at the camera, pulling all the attention. The rabbit was half off-frame. Most attention went to the cat’s face.

I redesigned it using AI-generated images, where I could control exactly where each animal looked. Dog looking at the camera. Cat looking right. Rabbit looking left. All the attention drawn into the center. Made a massive difference.

Creating The Perfect Image

I use AI all the time for creating images that do a specific job. My preferred tools are Midjourney and Gemini.

I like Midjourney because, visually, it creates stunning imagery. You can dial in the tone and style you want. The downside is that it is not great at following specific instructions.

So I produce an image in Midjourney that is close, then upload it to Gemini. Gemini is not as good at visual style, but it is much better at following instructions. “Make the guy reach here” or “Add glasses to this person.” I can get pretty much exactly what I want.

The other thing I love about Midjourney is that you can upload a photograph and say, “Replicate this style.” This keeps consistency across a website. I have a master image I use as a reference for all my site imagery to keep the style consistent.

Using AI For Content

Most clients give you terrible copy. Our job is to improve the user experience or conversion rate, and anything we do gets utterly undermined by bad copy.

I have completely stopped asking clients for copy since AI came along. Here is my process.

Build Everything Around Questions

Once I have my information architecture, I get AI to generate a massive list of questions users will ask. Then I run a top task analysis where people vote on which questions matter most.

I assign those questions to pages on the site. Every page gets a list of the questions it needs to answer.

Get Bullet Point Answers From Stakeholders

I spin up the content management system with a really basic theme. Just HTML with very basic formatting. I go through every page and assign the questions.

Then I go to my clients and say: “I do not want you to write copy. Just go through every page and bullet point answers to the questions. If the answer exists on the old site, copy and paste some text or link to it. But just bullet points.”

That is their job done. Pretty much.

Let AI Draft The Copy

Now I take control. I feed ChatGPT the questions and bullet points and say:

Act as an online copywriter. Write copy for a webpage that answers the question [question]. Use the following bullet points to answer that question: [bullet points]. Use the following guidelines: Aim for a ninth-grade reading level or below. Sentences should be short. Use plain language. Avoid jargon. Refer to the reader as you. Refer to the writer as us. Ensure the tone is friendly, approachable, and reassuring. The goal is to [goal]. Think deeply about your approach. Create a rubric and iterate until the copy is excellent. Only then, output it.

I often upload a full style guide as well, with details about how I want it to be written.

The output is genuinely good. As a first draft, it is excellent. Far better than what most stakeholders would give me.

Stakeholders Review And Provide Feedback

That goes into the website, and stakeholders can comment on it. Once I get their feedback, I take the original copy and all their comments back into ChatGPT and say, “Rewrite using these comments.”

Job done.

The great thing about this approach is that even if stakeholders make loads of changes, they are making changes to a good foundation. The overall quality still comes out better than if they started with a blank sheet.

It also makes things go smoother because you are not criticizing their content, where they get defensive. They are criticizing AI content.

Tools That Help

If your stakeholders are still giving you content, Hemingway Editor is brilliant. Copy and paste text in, and it tells you how readable and scannable it is. It highlights long sentences and jargon. You can use this to prove to clients that their content is not good web copy.

If you pay for the pro version, you get AI tools that will rewrite the copy to be more readable. It is excellent.

What This Means for You

Let me be clear about something. None of this is perfect. AI makes mistakes. It hallucinates. It produces bland output if you do not push it hard enough. It requires constant checking and challenging.

But here is what I know from two years of using this stuff daily. It has made me faster. It has made me better. It has freed me up to do more strategic thinking and less grunt work.

A report that would have taken me five days now takes three hours. That is not an exaggeration. That is real.

Overall, AI probably gives me a 25 to 33 percent increase in what I can do. That is significant.

Your value as a UX professional lies in your ideas, your questions, and your thinking. Not your ability to use Figma. Not your ability to manually review transcripts. Not your ability to write reports from scratch.

“

AI cannot innovate. It cannot make creative leaps. It cannot know whether its output is good. It cannot understand what it is like to be human.

That is where you come in. That is where you will always come in.

Start small. Do not try to learn everything at once. Just ask yourself throughout your day: Could I do this with AI? Try it. See what happens. Double-check everything. Learn what works and what does not.

Treat it like an enthusiastic intern with zero life experience. Give it clear instructions. Check its work. Make it try again. Challenge it. Push it further.

And remember, it is not going to take your job. It is going to change it. For the better, I think. As long as we learn to work with it rather than against it.

(yk)

How To Make Your UX Research Hard To Ignore

How To Make Your UX Research Hard To Ignore How To Make Your UX Research Hard To Ignore Vitaly Friedman 2025-10-16T13:00:00+00:00 2025-10-22T16:03:02+00:00 In the early days of my career, I believed that nothing wins an argument more effectively than strong and unbiased research. Surely facts […]

Accessibility

How To Make Your UX Research Hard To Ignore

Vitaly Friedman 2025-10-16T13:00:00+00:00

2025-10-22T16:03:02+00:00

In the early days of my career, I believed that nothing wins an argument more effectively than strong and unbiased research. Surely facts speak for themselves, I thought.

If I just get enough data, just enough evidence, just enough clarity on where users struggle — well, once I have it all and I present it all, it alone will surely change people’s minds, hearts, and beliefs. And, most importantly, it will help everyone see, understand, and perhaps even appreciate and commit to what needs to be done.

Well, it’s not quite like that. In fact, the stronger and louder the data, the more likely it is to be questioned. And there is a good reason for that, which is often left between the lines.

Research Amplifies Internal Flaws

Throughout the years, I’ve often seen data speaking volumes about where the business is failing, where customers are struggling, where the team is faltering — and where an urgent turnaround is necessary. It was right there, in plain sight: clear, loud, and obvious.

But because it’s so clear, it reflects back, often amplifying all the sharp edges and all the cut corners in all the wrong places. It reflects internal flaws, wrong assumptions, and failing projects — some of them signed off years ago, with secured budgets, big promotions, and approved headcounts. Questioning them means questioning authority, and often it’s a tough path to take.

As it turns out, strong data is very, very good at raising uncomfortable truths that most companies don’t really want to acknowledge. That’s why, at times, research is deemed “unnecessary,” or why we don’t get access to users, or why loud voices always win big arguments.

So even if data is presented with a lot of eagerness, gravity, and passion in that big meeting, it will get questioned, doubted, and explained away. Not because of its flaws, but because of hope, reluctance to change, and layers of internal politics.

This shows up most vividly in situations when someone raises concerns about the validity and accuracy of research. Frankly, it’s not that somebody is wrong and somebody is right. Both parties just happen to be right in a different way.

What To Do When Data Disagrees

We’ve all heard that data always tells a story. However, it’s never just a single story. People are complex, and pointing out a specific truth about them just by looking at numbers is rarely enough.

When data disagrees, it doesn’t mean that either is wrong. It’s just that different perspectives reveal different parts of a whole story that isn’t completed yet.

In digital products, most stories have 2 sides:

- Quantitative data ← What/When: behavior patterns at scale.

- Qualitative data ← Why/How: user needs and motivations.

- ↳ Quant usually comes from analytics, surveys, and experiments.

- ↳ Qual comes from tests, observations, and open-ended surveys.

Risk-averse teams overestimate the weight of big numbers in quantitative research. Users exaggerate the frequency and severity of issues that are critical for them. As Archana Shah noted, designers get carried away by users’ confident responses and often overestimate what people say and do.

And so, eventually, data coming from different teams paints a different picture. And when it happens, we need to reconcile and triangulate. With the former, we track what’s missing, omitted, or overlooked. With the latter, we cross-validate data — e.g., finding pairings of qual/quant streams of data, then clustering them together to see what’s there and what’s missing, and exploring from there.

And even with all of it in place and data conflicts resolved, we still need to do one more thing to make a strong argument: we need to tell a damn good story.

Facts Don’t Win Arguments, Stories Do

Research isn’t everything. Facts don’t win arguments — powerful stories do. But a story that starts with a spreadsheet isn’t always inspiring or effective. Perhaps it brings a problem into the spotlight, but it doesn’t lead to a resolution.

The very first thing I try to do in that big boardroom meeting is to emphasize what unites us — shared goals, principles, and commitments that are relevant to the topic at hand. Then, I show how new data confirms or confronts our commitments, with specific problems we believe we need to address.

When a question about the quality of data comes in, I need to show that it has been reconciled and triangulated already and discussed with other teams as well.

A good story has a poignant ending. People need to see an alternative future to trust and accept the data — and a clear and safe path forward to commit to it. So I always try to present options and solutions that we believe will drive change and explain our decision-making behind that.

They also need to believe that this distant future is within reach, and that they can pull it off, albeit under a tough timeline or with limited resources.

And: a good story also presents a viable, compelling, shared goal that people can rally around and commit to. Ideally, it’s something that has a direct benefit for them and their teams.

These are the ingredients of the story that I always try to keep in my mind when working on that big presentation. And in fact, data is a starting point, but it does need a story wrapped around it to be effective.

Wrapping Up

There is nothing more disappointing than finding a real problem that real people struggle with and facing the harsh reality of research not being trusted or valued.

We’ve all been there before. The best thing you can do is to be prepared: have strong data to back you up, include both quantitative and qualitative research — preferably with video clips from real customers — but also paint a viable future which seems within reach.

And sometimes nothing changes until something breaks. And at times, there isn’t much you can do about it unless you are prepared when it happens.

“Data doesn’t change minds, and facts don’t settle fights. Having answers isn’t the same as learning, and it for sure isn’t the same as making evidence-based decisions.”

— Erika Hall

Meet “How To Measure UX And Design Impact”

You can find more details on UX Research in Measure UX & Design Impact (8h), a practical guide for designers and UX leads to measure and show your UX impact on business. Use the code 🎟 IMPACT to save 20% off today. Jump to the details.

Video + UX Training

$ 495.00 $ 799.00

Get Video + UX Training

25 video lessons (8h) + Live UX Training.

100 days money-back-guarantee.

Video only

25 video lessons (8h). Updated yearly.

Also available as a UX Bundle with 2 video courses.

Useful Resources

- “How to Present Research So Stakeholders Sit Up and Take Action”, by Nikki Anderson

- “What To Do When Data Disagrees”, by Subhasree Chatterjee, Archana Shah, Sanket Shukl, and Jason Bressler

- “Mixed-Method UX Research”, by Raschin Fatemi

- “A Step-by-Step Framework For Mixed-Method Research”, by Jeremy Williams

- “The Ultimate Guide To Mixed Methods”, by Ben Wiedmaier

- Survey Design Cheatsheet, by yours truly

- Useful Calculators For UX Research, by yours truly

- Beyond Measure, by Erika Hall

Useful Books

- Just Enough Research, by Erika Hall

- Designing Surveys That Work, by Caroline Jarrett

- Designing Quality Survey Questions, by Sheila B. Robinson

(yk)

Intent Prototyping: A Practical Guide To Building With Clarity (Part 2)

Intent Prototyping: A Practical Guide To Building With Clarity (Part 2) Intent Prototyping: A Practical Guide To Building With Clarity (Part 2) Yegor Gilyov 2025-10-03T10:00:00+00:00 2025-10-08T15:02:36+00:00 In Part 1 of this series, we explored the “lopsided horse” problem born from mockup-centric design and demonstrated how […]

Accessibility

Intent Prototyping: A Practical Guide To Building With Clarity (Part 2)

Yegor Gilyov 2025-10-03T10:00:00+00:00

2025-10-08T15:02:36+00:00

In Part 1 of this series, we explored the “lopsided horse” problem born from mockup-centric design and demonstrated how the seductive promise of vibe coding often leads to structural flaws. The main question remains:

How might we close the gap between our design intent and a live prototype, so that we can iterate on real functionality from day one, without getting caught in the ambiguity trap?

In other words, we need a way to build prototypes that are both fast to create and founded on a clear, unambiguous blueprint.

The answer is a more disciplined process I call Intent Prototyping (kudos to Marco Kotrotsos, who coined Intent-Oriented Programming). This method embraces the power of AI-assisted coding but rejects ambiguity, putting the designer’s explicit intent at the very center of the process. It receives a holistic expression of intent (sketches for screen layouts, conceptual model description, boxes-and-arrows for user flows) and uses it to generate a live, testable prototype.

This method solves the concerns we’ve discussed in Part 1 in the best way possible:

- Unlike static mockups, the prototype is fully interactive and can be easily populated with a large amount of realistic data. This lets us test the system’s underlying logic as well as its surface.