Setting And Persisting Color Scheme Preferences With CSS And A “Touch” Of JavaScript

There are many ways to approach a “Dark Mode” feature that respects a user’s system color scheme preferences and allows for per-site customization. With recent developments in CSS, core function

Javascript

Designing For Agentic AI: Practical UX Patterns For Control, Consent, And Accountability

Autonomy is an output of a technical system. Trustworthiness is an output of a design process. Here are concrete design patterns, operational frameworks, and organizational practices for building agen

Ux

Designing A Streak System: The UX And Psychology Of Streaks

What makes streaks so powerful and addictive? To design them well, you need to understand how they align with human psychology. Victor Ayomipo breaks down the UX and design principles behind effective

Ux

Setting And Persisting Color Scheme Preferences With CSS And A “Touch” Of JavaScript

There are many ways to approach a “Dark Mode” feature that respects a user’s system color scheme preferences and allows for per-site customization. With recent developments in CSS, core function

Javascript

Setting And Persisting Color Scheme Preferences With CSS And A “Touch” Of JavaScript

Henry Bley-Vroman

Many modern websites give users the power to set a site-specific color scheme preference. A basic implementation is straightforward with JavaScript: listen for when a user changes a checkbox or clicks a button, toggle a class (or attribute) on the <body> element in response, and write the styles for that class to override design with a different color scheme.

CSS’s new :has() pseudo-class, supported by major browsers since December 2023, opens many doors for front-end developers. I’m especially excited about leveraging it to modify UI in response to user interaction without JavaScript. Where previously we have used JavaScript to toggle classes or attributes (or to set styles directly), we can now pair :has() selectors with HTML’s native interactive elements.

Supporting a color scheme preference, like “Dark Mode,” is a great use case. We can use a <select> element anywhere that toggles color schemes based on the selected <option> — no JavaScript needed, save for a sprinkle to save the user’s choice, which we’ll get to further in.

Respecting System Preferences

First, we’ll support a user’s system-wide color scheme preferences by adopting a “Light Mode”-first approach. In other words, we start with a light color scheme by default and swap it out for a dark color scheme for users who prefer it.

The prefers-color-scheme media feature detects the user’s system preference. Wrap “dark” styles in a prefers-color-scheme: dark media query.

selector { /* light styles */ @media (prefers-color-scheme: dark) { /* dark styles */ } } Next, set the color-scheme property to match the preferred color scheme. Setting color-scheme: dark switches the browser into its built-in dark mode, which includes a black default background, white default text, “dark” styles for scrollbars, and other elements that are difficult to target with CSS, and more. I’m using CSS variables to hint that the value is dynamic — and because I like the browser developer tools experience — but plain color-scheme: light and color-scheme: dark would work fine.

:root { /* light styles here */ color-scheme: var(--color-scheme, light); /* system preference is "dark" */ @media (prefers-color-scheme: dark) { --color-scheme: dark; /* any additional dark styles here */ } } Giving Users Control

Now, to support overriding the system preference, let users choose between light (default) and dark color schemes at the page level.

HTML has native elements for handling user interactions. Using one of those controls, rather than, say, a <div> nest, improves the chances that assistive tech users will have a good experience. I’ll use a <select> menu with options for “system,” “light,” and “dark.” A group of <input type="radio"> would work, too, if you wanted the options right on the surface instead of a dropdown menu.

<select id="color-scheme"> <option value="system" selected>System</option> <option value="light">Light</option> <option value="dark">Dark</option> </select> Before CSS gained :has(), responding to the user’s selected <option> required JavaScript, for example, setting an event listener on the <select> to toggle a class or attribute on <html> or <body>.

But now that we have :has(), we can now do this with CSS alone! You’ll save spending any of your performance budget on a dark mode script, plus the control will work even for users who have disabled JavaScript. And any “no-JS” folks on the project will be satisfied.

What we need is a selector that applies to the page when it :has() a select menu with a particular [value]:checked. Let’s translate that into CSS:

:root:has(select option[value="dark"]:checked)We’re defaulting to a light color scheme, so it’s enough to account for two possible dark color scheme scenarios:

- The page-level color preference is “system,” and the system-level preference is “dark.”

- The page-level color preference is “dark”.

The first one is a page-preference-aware iteration of our prefers-color-scheme: dark case. A “dark” system-level preference is no longer enough to warrant dark styles; we need a “dark” system-level preference and a “follow the system-level preference” at the page-level preference. We’ll wrap the prefers-color-scheme media query dark scheme styles with the :has() selector we just wrote:

:root { /* light styles here */ color-scheme: var(--color-scheme, light); /* page preference is "system", and system preference is "dark" */ @media (prefers-color-scheme: dark) { &:has(#color-scheme option[value="system"]:checked) { --color-scheme: dark; /* any additional dark styles, again */ } } } Notice that I’m using CSS Nesting in that last snippet. Baseline 2023 has it pegged as “Newly available across major browsers” which means support is good, but at the time of writing, support on Android browsers not included in Baseline’s core browser set is limited. You can get the same result without nesting.

:root { /* light styles */ color-scheme: var(--color-scheme, light); /* page preference is "dark" */ &:has(#color-scheme option[value="dark"]:checked) { --color-scheme: dark; /* any additional dark styles */ } } For the second dark mode scenario, we’ll use nearly the exact same :has() selector as we did for the first scenario, this time checking whether the “dark” option — rather than the “system” option — is selected:

:root { /* light styles */ color-scheme: var(--color-scheme, light); /* page preference is "dark" */ &:has(#color-scheme option[value="dark"]:checked) { --color-scheme: dark; /* any additional dark styles */ } /* page preference is "system", and system preference is "dark" */ @media (prefers-color-scheme: dark) { &:has(#color-scheme option[value="system"]:checked) { --color-scheme: dark; /* any additional dark styles, again */ } } } Now the page’s styles respond to both changes in users’ system settings and user interaction with the page’s color preference UI — all with CSS!

But the colors change instantly. Let’s smooth the transition.

Respecting Motion Preferences

Instantaneous style changes can feel inelegant in some cases, and this is one of them. So, let’s apply a CSS transition on the :root to “ease” the switch between color schemes. (Transition styles at the :root will cascade down to the rest of the page, which may necessitate adding transition: none or other transition overrides.)

Note that the CSS color-scheme property does not support transitions.

:root { transition-duration: 200ms; transition-property: /* properties changed by your light/dark styles */; } Not all users will consider the addition of a transition a welcome improvement. Querying the prefers-reduced-motion media feature allows us to account for a user’s motion preferences. If the value is set to reduce, then we remove the transition-duration to eliminate unwanted motion.

:root { transition-duration: 200ms; transition-property: /* properties changed by your light/dark styles */; @media screen and (prefers-reduced-motion: reduce) { transition-duration: none; } } Transitions can also produce poor user experiences on devices that render changes slowly, for example, ones with e-ink screens. We can extend our “no motion condition” media query to account for that with the update media feature. If its value is slow, then we remove the transition-duration.

:root { transition-duration: 200ms; transition-property: /* properties changed by your light/dark styles */; @media screen and (prefers-reduced-motion: reduce), (update: slow) { transition-duration: 0s; } } Let’s try out what we have so far in the following demo. Notice that, to work around color-scheme’s lack of transition support, I’ve explicitly styled the properties that should transition during theme changes.

See the Pen [CSS-only theme switcher (requires :has()) [forked]](https://codepen.io/smashingmag/pen/YzMVQja) by Henry.

Not bad! But what happens if the user refreshes the pages or navigates to another page? The reload effectively wipes out the user’s form selection, forcing the user to re-make the selection. That may be acceptable in some contexts, but it’s likely to go against user expectations. Let’s bring in JavaScript for a touch of progressive enhancement in the form of…

Persistence

Here’s a vanilla JavaScript implementation. It’s a naive starting point — the functions and variables aren’t encapsulated but are instead properties on window. You’ll want to adapt this in a way that fits your site’s conventions, framework, library, and so on.

When the user changes the color scheme from the <select> menu, we’ll store the selected <option> value in a new localStorage item called "preferredColorScheme". On subsequent page loads, we’ll check localStorage for the "preferredColorScheme" item. If it exists, and if its value corresponds to one of the form control options, we restore the user’s preference by programmatically updating the menu selection.

/* * If a color scheme preference was previously stored, * select the corresponding option in the color scheme preference UI * unless it is already selected. */ function restoreColorSchemePreference() { const colorScheme = localStorage.getItem(colorSchemeStorageItemName); if (!colorScheme) { // There is no stored preference to restore return; } const option = colorSchemeSelectorEl.querySelector(`[value=${colorScheme}]`); if (!option) { // The stored preference has no corresponding option in the UI. localStorage.removeItem(colorSchemeStorageItemName); return; } if (option.selected) { // The stored preference's corresponding menu option is already selected return; } option.selected = true; } /* * Store an event target's value in localStorage under colorSchemeStorageItemName */ function storeColorSchemePreference({ target }) { const colorScheme = target.querySelector(":checked").value; localStorage.setItem(colorSchemeStorageItemName, colorScheme); } // The name under which the user's color scheme preference will be stored. const colorSchemeStorageItemName = "preferredColorScheme"; // The color scheme preference front-end UI. const colorSchemeSelectorEl = document.querySelector("#color-scheme"); if (colorSchemeSelectorEl) { restoreColorSchemePreference(); // When the user changes their color scheme preference via the UI, // store the new preference. colorSchemeSelectorEl.addEventListener("input", storeColorSchemePreference); } Let’s try that out. Open this demo (perhaps in a new window), use the menu to change the color scheme, and then refresh the page to see your preference persist:

See the Pen [CSS-only theme switcher (requires :has()) with JS persistence [forked]](https://codepen.io/smashingmag/pen/GRLmEXX) by Henry.

If your system color scheme preference is “light” and you set the demo’s color scheme to “dark,” you may get the light mode styles for a moment immediately after reloading the page before the dark mode styles kick in. That’s because CodePen loads its own JavaScript before the demo’s scripts. That is out of my control, but you can take care to improve this persistence on your projects.

Persistence Performance Considerations

Where things can get tricky is restoring the user’s preference immediately after the page loads. If the color scheme preference in localStorage is different from the user’s system-level color scheme preference, it’s possible the user will see the system preference color scheme before the page-level preference is restored. (Users who have selected the “System” option will never get that flash; neither will those whose system settings match their selected option in the form control.)

If your implementation is showing a “flash of inaccurate color theme”, where is the problem happening? Generally speaking, the earlier the scripts appear on the page, the lower the risk. The “best option” for you will depend on your specific stack, of course.

What About Browsers That Don’t Support :has()?

All major browsers support :has() today Lean into modern platforms if you can. But if you do need to consider legacy browsers, like Internet Explorer, there are two directions you can go: either hide or remove the color scheme picker for those browsers or make heavier use of JavaScript.

If you consider color scheme support itself a progressive enhancement, you can entirely hide the selection UI in browsers that don’t support :has():

@supports not selector(:has(body)) { @media (prefers-color-scheme: dark) { :root { /* dark styles here */ } } #color-scheme { display: none; } } Otherwise, you’ll need to rely on a JavaScript solution not only for persistence but for the core functionality. Go back to that traditional event listener toggling a class or attribute.

The CSS-Tricks “Complete Guide to Dark Mode” details several alternative approaches that you might consider as well when working on the legacy side of things.

Designing For Agentic AI: Practical UX Patterns For Control, Consent, And Accountability

Autonomy is an output of a technical system. Trustworthiness is an output of a design process. Here are concrete design patterns, operational frameworks, and organizational practices for building agen

Ux

Designing For Agentic AI: Practical UX Patterns For Control, Consent, And Accountability

Victor Yocco

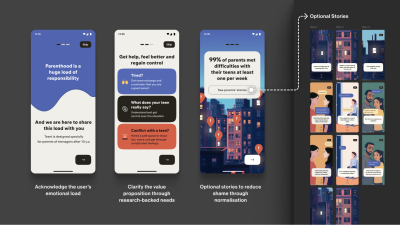

In the first part of this series, we established the fundamental shift from generative to agentic artificial intelligence. We explored why this leap from suggesting to acting demands a new psychological and methodological toolkit for UX researchers, product managers, and leaders. We defined a taxonomy of agentic behaviors, from suggesting to acting autonomously, outlined the essential research methods, defined the risks of agentic sludge, and established the accountability metrics required to navigate this new territory. We covered the what and the why.

Now, we move from the foundational to the functional. This article provides the how: the concrete design patterns, operational frameworks, and organizational practices essential for building agentic systems that are not only powerful but also transparent, controllable, and worthy of user trust. If our research is the diagnostic tool, these patterns are the treatment plan. They are the practical mechanisms through which we can give users a palpable sense of control, even as we grant AI unprecedented autonomy. The goal is to create an experience where autonomy feels like a privilege granted by the user, not a right seized by the system.

Core UX Patterns For Agentic Systems

Designing for agentic AI is designing for a relationship. This relationship, like any successful partnership, must be built on clear communication, mutual understanding, and established boundaries.

To manage the shift from suggestion to action, we utilize six patterns that follow the functional lifecycle of an agentic interaction:

- Pre-Action (Establishing Intent)

The Intent Preview and Autonomy Dial ensure the user defines the plan and the agent’s boundaries before anything happens. - In-Action (Providing Context)

The Explainable Rationale and Confidence Signal maintain transparency while the agent works, showing the “why” and “how certain.” - Post-Action (Safety and Recovery)

The Action Audit & Undo and Escalation Pathway provide a safety net for errors or high-ambiguity moments.

Below, we will cover each pattern in detail, including recommendations for metrics for success. These targets are representative benchmarks based on industry standards; adjust them based on your specific domain risk.

1. The Intent Preview: Clarifying the What and How

This pattern is the conversational equivalent of saying, “Here’s what I’m about to do. Are you okay with that?” It’s the foundational moment of seeking consent in the user-agent relationship.

Before an agent takes any significant action, the user must have a clear, unambiguous understanding of what is about to happen. The Intent Preview, or Plan Summary, establishes informed consent. It is the conversational pause before action, transforming a black box of autonomous processes into a transparent, reviewable plan.

Psychological Underpinning

Presenting a plan before action reduces cognitive load and eliminates surprise, giving users a moment to verify the agent truly understands their intent.

Anatomy of an Effective Intent Preview:

- Clarity and Conciseness

The preview must be immediately digestible. It should summarize the primary actions and outcomes in plain language, avoiding technical jargon. For instance, instead of “Executing API call to cancel_booking(id: 4A7B),” it should state, “Cancel flight AA123 to San Francisco.” - Sequential Steps

For multi-step operations, the preview should outline the key phases. This reveals the agent’s logic and allows users to spot potential issues in the proposed sequence. - Clear User Actions

The preview is a decision point, not just a notification. It must be accompanied by a clear set of choices. It’s a moment of intentional friction, a ‘speed bump’ in the process designed to ensure the user is making a conscious choice, particularly for irreversible or high-stakes actions.

Let’s revisit our travel assistant scenario from the first part of this series. We use this proactive assistant to illustrate how an agent handles a flight cancellation. The agent has detected a flight cancellation and has formulated a recovery plan.

The Intent Preview would look something like this:

Proposed Plan for Your Trip Disruption

I’ve detected that your 10:05 AM flight has been canceled. Here’s what I plan to do:

- Cancel Flight UA456

Process refund and confirm cancellation details.- Rebook on Flight DL789

Book a confirmed seat on a 2:30 PM non-stop flight, as this is the next available non-stop flight with a confirmed seat.- Update Hotel Reservation

Notify the Marriott that you will be arriving late.- Email Updated Itinerary

Send the new flight and hotel details to you and your assistant, Jane Doe.[ Proceed with this Plan ] [ Edit Plan ] [ Handle it Myself ]

This preview is effective because it provides a complete picture, from cancellation to communication, and offers three distinct paths forward: full consent (Proceed), a desire for modification (Edit Plan), or a full override (Handle it Myself). This multifaceted control is the bedrock of trust.

When to Prioritize This Pattern

This pattern is non-negotiable for any action that is irreversible (e.g., deleting user data), involves a financial transaction of any amount, shares information with other people or systems, or makes a significant change that a user cannot easily undo.

Risk of Omission

Without this, users feel ambushed by the agent’s actions and will disable the feature to regain control.

Metrics for Success:

- Acceptance Ratio

Plans Accepted Without Edit / Total Plans Displayed. Target > 85%. - Override Frequency

Total Handle it Myself Clicks / Total Plans Displayed. A rate > 10% triggers a model review. - Recall Accuracy

Percentage of test participants who can correctly list the plan’s steps 10 seconds after the preview is hidden.

Applying This to High-Stakes Domains

While travel plans are a relatable baseline, this pattern becomes indispensable in complex, high-stakes environments where an error results in more than an inconvenience for an individual traveling. Many of us work in settings where wrong decisions may result in a system outage, putting a patient’s safety at risk, or numerous other catastrophic outcomes that unreliable technology would introduce.

Consider a DevOps Release Agent tasked with managing cloud infrastructure. In this context, the Intent Preview acts as a safety barrier against accidental downtime.

In this interface, the specific terminology (Drain Traffic, Rollback) replaces generalities, and the actions are binary and impactful. The user authorizes a major operational shift based on the agent’s logic, rather than approving a suggestion.

2. The Autonomy Dial: Calibrating Trust With Progressive Authorization

Every healthy relationship has boundaries. The Autonomy Dial is how the user establishes it with their agent, defining what they are comfortable with the agent handling on its own.

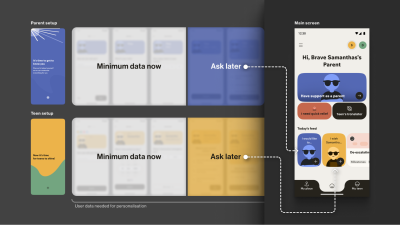

Trust is not a binary switch; it’s a spectrum. A user might trust an agent to handle low-stakes tasks autonomously but demand full confirmation for high-stakes decisions. The Autonomy Dial, a form of progressive authorization, allows users to set their preferred level of agent independence, making them active participants in defining the relationship.

Psychological Underpinning

Allowing users to tune the agent’s autonomy grants them a locus of control, letting them match the system’s behavior to their personal risk tolerance.

Implementation

This can be implemented as a simple, clear setting within the application, ideally on a per-task-type basis. Using the taxonomy from our first article, the settings could be:

- Observe & Suggest

I want to be notified of opportunities or issues, but the agent will never propose a plan. - Plan & Propose

The agent can create plans, but I must review every one before any action is taken. - Act with Confirmation

For familiar tasks, the agent can prepare actions, and I will give a final go/no-go confirmation. - Act Autonomously

For pre-approved tasks (e.g., disputing charges under $50), the agent can act independently and notify me after the fact.

An email assistant, for example, could have a separate autonomy dial for scheduling meetings versus sending emails on the user’s behalf. This granularity is key, as it reflects the nuanced reality of a user’s trust.

When to Prioritize This Pattern

Prioritize this in systems where tasks vary widely in risk and personal preference (e.g., financial management tools, communication platforms). It is essential for onboarding, allowing users to start with low autonomy and increase it as their confidence grows.

Risk of Omission

Without this, users who experience a single failure will abandon the agent completely rather than simply dialing back its permissions.

Metrics for Success:

- Trust Density

Percentage breakdown of users per setting (e.g., 20% Suggest, 50% Confirm, 30% Auto). - Setting Churn

Number of Setting Changes / Total Active Users per month. High churn indicates trust volatility.

3. The Explainable Rationale: Answering Why?

After taking an action, a good partner explains their reasoning. This pattern is the open communication that follows an action, answering Why? before it’s even asked. “I did that because you’ve told me in the past that you prefer X.”

When an agent acts, especially autonomously, the immediate question in the user’s mind is often, Why did it do that? The Explainable Rationale pattern proactively answers this question, providing a concise justification for the agent’s decisions. This is not a technical log file. In my first article of this series, we discussed translating system primitives into user-facing language to prevent deception. This pattern is the practical application of that principle. It transforms the raw logic into a human-readable explanation grounded in the user’s own stated preferences and prior inputs.

Psychological Underpinning

When an agent’s actions are explainable, they feel logical rather than random, helping the user build an accurate mental model of how the agent thinks.

Effective Rationales:

- Grounded in Precedent

The best explanations link back to a rule, preference, or prior action. - Simple and Direct

Avoid complex conditional logic. Use a simple “Because you said X, I did Y” structure.

Returning to the travel example, after the flight is rebooked autonomously, the user might see this in their notification feed:

I’ve rebooked your canceled flight.

- New Flight: Delta 789, departing at 2:30 PM.

- Why I took this action:

- Your original flight was canceled by the airline.

- You’ve pre-approved autonomous rebooking for same-day, non-stop flights.

[ View New Itinerary ] [ Undo this Action ]

The rationale is clear, defensible, and reinforces the idea that the agent is operating within the boundaries the user established.

When to Prioritize This Pattern

Prioritize it for any autonomous action where the reasoning isn’t immediately obvious from the context, especially for actions that happen in the background or are triggered by an external event (like the flight cancellation example).

Risk of Omission

Without this, users interpret valid autonomous actions as random behavior or ‘bugs,’ preventing them from forming a correct mental model.

Metrics for Success:

- Why? Ticket Volume

Number of support tickets tagged “Agent Behavior — Unclear” per 1,000 active users. - Rationale Validation

Percentage of users who rate the explanation as ‘Helpful’ in post-interaction microsurveys.

4. The Confidence Signal

This pattern is about the agent being self-aware in the relationship. By communicating its own confidence, it helps the user decide when to trust its judgment and when to apply more scrutiny.

To help users calibrate their own trust, the agent should surface its own confidence in its plans and actions. This makes the agent’s internal state more legible and helps the user decide when to scrutinize a decision more closely.

Psychological Underpinning

Surfacing uncertainty helps prevent automation bias, encouraging users to scrutinize low-confidence plans rather than blindly accepting them.

Implementation:

- Confidence Score

A simple percentage (e.g., Confidence: 95%) can be a quick, scannable indicator. - Scope Declaration

A clear statement of the agent’s area of expertise (e.g., Scope: Travel bookings only) helps manage user expectations and prevents them from asking the agent to perform tasks it’s not designed for. - Visual Cues

A green checkmark can denote high confidence, while a yellow question mark can indicate uncertainty, prompting the user to review more carefully.

When to Prioritize This Pattern

Prioritize when the agent’s performance can vary significantly based on the quality of input data or the ambiguity of the task. It is especially valuable in expert systems (e.g., medical aids, code assistants) where a human must critically evaluate the AI’s output.

Risk of Omission

Without this, users will fall victim to automation bias, blindly accepting low-confidence hallucinations, or anxiously double-check high-confidence work.

Metrics for Success:

- Calibration Score

Pearson correlation between Model Confidence Score and User Acceptance Rate. Target > 0.8. - Scrutiny Delta

Difference between the average review time of low-confidence plans and high-confidence plans. Expected to be positive (e.g., +12 seconds).

5. The Action Audit & Undo: The Ultimate Safety Net

Trust requires knowing you can recover from a mistake. The Undo function is the ultimate relationship safety net, assuring the user that even if the agent misunderstands, the consequences are not catastrophic.

The single most powerful mechanism for building user confidence is the ability to easily reverse an agent’s action. A persistent, easy-to-read Action Audit log, with a prominent Undo button for every possible action, is the ultimate safety net. It dramatically lowers the perceived risk of granting autonomy.

Psychological Underpinning

Knowing that a mistake can be easily undone creates psychological safety, encouraging users to delegate tasks without fear of irreversible consequences.

Design Best Practices:

- Timeline View

A chronological log of all agent-initiated actions is the most intuitive format. - Clear Status Indicators

Show whether an action was successful, is in progress, or has been undone. - Time-Limited Undos

For actions that become irreversible after a certain point (e.g., a non-refundable booking), the UI must clearly communicate this time window (e.g., Undo available for 15 minutes). This transparency about the system’s limitations is just as important as the undo capability itself. Being honest about when an action becomes permanent builds trust.

When to Prioritize This Pattern

This is a foundational pattern that should be implemented in nearly all agentic systems. It is absolutely non-negotiable when introducing autonomous features or when the cost of an error (financial, social, or data-related) is high.

Risk of Omission

Without this, one error permanently destroys trust, as users realize they have no safety net.

Metrics for Success:

- Reversion Rate

Undone Actions / Total Actions Performed. If the Reversion Rate > 5% for a specific task, disable automation for that task. - Safety Net Conversion

Percentage of users who upgrade to Act Autonomously within 7 days of successfully using Undo.

6. The Escalation Pathway: Handling Uncertainty Gracefully

A smart partner knows when to ask for help instead of guessing. This pattern allows the agent to handle ambiguity gracefully by escalating to the user, demonstrating a humility that builds, rather than erodes, trust.

Even the most advanced agent will encounter situations where it is uncertain about the user’s intent or the best course of action. How it handles this uncertainty is a defining moment. A well-designed agent doesn’t guess; it escalates.

Psychological Underpinning

When an agent acknowledges its limits rather than guessing, it builds trust by respecting the user’s authority in ambiguous situations.

Escalation Patterns Include:

- Requesting Clarification

“You mentioned ‘next Tuesday.’ Do you mean September 30th or October 7th?” - Presenting Options

“I found three flights that match your criteria. Which one looks best to you?” - Requesting Human Intervention

For high-stakes or highly ambiguous tasks, the agent should have a clear pathway to loop in a human expert or support agent. The prompt might be: “This transaction seems unusual, and I’m not confident about how to proceed. Would you like me to flag this for a human agent to review?”

When to Prioritize This Pattern

Prioritize in domains where user intent can be ambiguous or highly context-dependent (e.g., natural language interactions, complex data queries). Use this whenever the agent operates with incomplete information or when multiple correct paths exist.

Risk of Omission

Without this, the agent will eventually make a confident, catastrophic guess that alienates the user.

Metrics for Success:

- Escalation Frequency

Agent Requests for Help / Total Tasks. Healthy range: 5-15%. - Recovery Success Rate

Tasks Completed Post-Escalation / Total Escalations. Target > 90%.

| Pattern | Best For | Primary Risk | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intent Preview | Irreversible or financial actions | User feels ambushed | >85% Acceptance Rate |

| Autonomy Dial | Tasks with variable risk levels | Total feature abandonment | Setting Churn |

| Explainable Rationale | Background or autonomous tasks | User perceives bugs | “Why?” Ticket Volume |

| Confidence Signal | Expert or high-stakes systems | Automation bias | Scrutiny Delta |

| Action Audit & Undo | All agentic systems | Permanent loss of trust | <5% Reversion Rate |

| Escalation Pathway | Ambiguous user intent | Confident, catastrophic guesses | >90% Recovery Success |

Table 1: Summary of Agentic AI UX patterns. Remember to adjust the metrics based on your specific domain risk and needs.

Designing for Repair and Redress

This is learning how to apologize effectively. A good apology acknowledges the mistake, fixes the damage, and promises to learn from it.

Errors are not a possibility; they are an inevitability.

“

Empathic Apologies and Clear Remediation

When an agent makes a mistake, the error message is the apology. It must be designed with psychological precision. This moment is a critical opportunity to demonstrate accountability. From a service design perspective, this is where companies can use the service recovery paradox: the phenomenon where a customer who experiences a service failure, followed by a successful and empathetic recovery, can actually become more loyal than a customer who never experienced a failure at all. A well-handled mistake can be a more powerful trust-building event than a long history of flawless execution.

The key is treating the error as a relationship rupture that needs to be mended. This involves:

- Acknowledge the Error

The message should state clearly and simply that a mistake was made.

Example: I incorrectly transferred funds. - State the Immediate Correction

Immediately follow up with the remedial action.

Example: I have reversed the action, and the funds have been returned to your account. - Provide a Path for Further Help

Always offer a clear link to human support. This de-escalates frustration and shows that there is a system of accountability beyond the agent itself.

A well-designed repair UI might look like this:

We made a mistake on your recent transfer.

I apologize. I transferred $250 to the wrong account.✔ Corrective Action: The transfer has been reversed, and your $250 has been refunded.

✔ Next Steps: The incident has been flagged for internal review to prevent it from happening again.Need further help? [ Contact Support ]

Building the Governance Engine for Safe Innovation

The design patterns described above are the user-facing controls, but they cannot function effectively without a robust internal support structure. This is not about creating bureaucratic hurdles; it is about building a strategic advantage. An organization with a mature governance framework can ship more ambitious agentic features with greater speed and confidence, knowing that the necessary guardrails are in place to mitigate brand risk. This governance engine turns safety from a checklist into a competitive asset.

This engine should function as a formal governance body, an Agentic AI Ethics Council, comprising a cross-functional alliance of UX, Product, and Engineering, with vital support from Legal, Compliance, and Support. In smaller organizations, these ‘Council’ roles often collapse into a single triad of Product, Engineering, and Design leads.

A Checklist for Governance

- Legal/Compliance

This team is the first line of defense, ensuring the agent’s potential actions stay within regulatory and legal boundaries. They help define the hard no-go zones for autonomous action. - Product

The product manager is the steward of the agent’s purpose. They define and monitor its operational boundaries through a formal autonomy policy that documents what the agent is and is not allowed to do. They own the Agent Risk Register. - UX Research

This team is the voice of the user’s trust and anxiety. They are responsible for a recurring process for running trust calibration studies, simulated misbehavior tests, and qualitative interviews to understand the user’s evolving mental model of the agent. - Engineering

This team builds the technical underpinnings of trust. They must architect the system for robust logging, one-click undo functionality, and the hooks needed to generate clear, explainable rationales. - Support

These teams are on the front lines of failure. They must be trained and equipped to handle incidents caused by agent errors, and they must have a direct feedback loop to the Ethics Council to report on real-world failure patterns.

This governance structure should maintain a set of living documents, including an Agent Risk Register that proactively identifies potential failure modes, Action Audit Logs that are regularly reviewed, and the formal Autonomy Policy Documentation.

Where to Start: A Phased Approach for Product Leaders

For product managers and executives, integrating agentic AI can feel like a monumental task. The key is to approach it not as a single launch, but as a phased journey of building both technical capability and user trust in parallel. This roadmap allows your organization to learn and adapt, ensuring each step is built on a solid foundation.

Phase 1: Foundational Safety (Suggest & Propose)

The initial goal is to build the bedrock of trust without taking significant autonomous risks. In this phase, the agent’s power is limited to analysis and suggestion.

- Implement a rock-solid Intent Preview: This is your core interaction model. Get users comfortable with the idea of the agent formulating plans, while keeping the user in full control of execution.

- Build the Action Audit & Undo infrastructure: Even if the agent isn’t acting autonomously yet, build the technical scaffolding for logging and reversal. This prepares your system for the future and builds user confidence that a safety net exists.

Phase 2: Calibrated Autonomy (Act with Confirmation)

Once users are comfortable with the agent’s proposals, you can begin to introduce low-risk autonomy. This phase is about teaching users how the agent thinks and letting them set their own pace.

- Introduce the Autonomy Dial with limited settings: Start by allowing users to grant the agent the power to Act with Confirmation.

- Deploy the Explainable Rationale: For every action the agent prepares, provide a clear explanation. This demystifies the agent’s logic and reinforces that it is operating based on the user’s own preferences.

Phase 3: Proactive Delegation (Act Autonomously)

This is the final step, taken only after you have clear data from the previous phases demonstrating that users trust the system.

- Enable Act Autonomously for specific, pre-approved tasks: Use the data from Phase 2 (e.g., high Proceed rates, low Undo rates) to identify the first set of low-risk tasks that can be fully automated.

- Monitor and Iterate: The launch of autonomous features is not the end, but the beginning of a continuous cycle of monitoring performance, gathering user feedback, and refining the agent’s scope and behavior based on real-world data.

Design As The Ultimate Safety Lever

The emergence of agentic AI represents a new frontier in human-computer interaction. It promises a future where technology can proactively reduce our burdens and streamline our lives. But this power comes with profound responsibility.

“

As UX professionals, product managers, and leaders, our role is to act as the stewards of that trust. By implementing clear design patterns for control and consent, designing thoughtful pathways for repair, and building robust governance frameworks, we create the essential safety levers that make agentic AI viable. We are not just designing interfaces; we are architecting relationships. The future of AI’s utility and acceptance rests on our ability to design these complex systems with wisdom, foresight, and a deep-seated respect for the user’s ultimate authority.

Designing A Streak System: The UX And Psychology Of Streaks

What makes streaks so powerful and addictive? To design them well, you need to understand how they align with human psychology. Victor Ayomipo breaks down the UX and design principles behind effective

Ux

Designing A Streak System: The UX And Psychology Of Streaks

Victor Ayomipo

I’m sure you’ve heard of streaks or used an app with one. But ever wondered why streaks are so popular and powerful? Well, there is the obvious one that apps want as much of your attention as possible, but aside from that, did you know that when the popular learning app Duolingo introduced iOS widgets to display streaks, user commitment surged by 60%. Sixty percent is a massive shift in behaviour and demonstrates how “streak” patterns can be used to increase engagement and drive usage.

At its most basic, a streak is the number of consecutive days that a user completes a specific activity. Some people also define it as a “gamified” habit or a metric designed to encourage consistent usage.

But streaks transcend beyond being a metric or a record in an app; it is more psychological than that. Human instincts are easy to influence with the right factors. Look at these three factors: progress, pride, and fear of missing out (commonly called FOMO). What do all these have in common? Effort. The more effort you put into something, the more it shapes your identity, and that is how streaks crosses into the world of behavioural psychology.

Now, with great power comes great responsibility, and because of that, there’s a dark side to streaks.

In this article, we’ll be going into the psychology, UX, and design principles behind building an effective streak system. We’ll look at (1) why our brains almost instinctively respond to streak activity, (2) how to design streaks in ways that genuinely help users, and (3) the technical work involved in building a streak pattern.

The Psychology Behind Streaks

To design and build an effective streak system, we need to understand how it aligns with how our brains are wired. Like, what makes it so effective to the extent that we feel so much intense dedication to protect our streaks?

There are three interesting, well-documented psychology principles that support what makes streaks so powerful and addictive.

Loss Aversion

This is probably the strongest force behind streaks. I say this because most times, you almost can’t avoid this in life.

Think of it this way: If a friend gives you $100, you’d be happy. But if you lost $100 from your wallet, that would hurt way more. The emotional weight of those situations isn’t equal. Loss hurts way more than gain feels good.

Let’s take it further and say that I give you $100 and ask you to play a gamble. There’s a 50% chance you win another $100 and a 50% chance you lose the original $100. Would you take it? I wouldn’t. Most people wouldn’t. That’s loss aversion.

If you think about it, it is logical, it is understandable, it is human.

The concept behind loss aversion is that we feel the pain of losing something twice as much as the pleasure of gaining something of equal value. In psychological terms, loss lingers more than gains do.

You probably see how this relates to streaks. To build a noticeable streak, it requires effort; as a streak grows, the motivation behind it begins to fade; or more accurately, it starts to become secondary.

Here’s an example: Say your friend has a three-day streak closing their “Move Rings” on their Apple Watch. They have almost nothing to lose beyond wanting to achieve their goal and be consistent. At the same time, you have an impressive 219-day streak going. Chances are that you are trapped by the fear of losing it. You most likely aren’t thinking about the achievement at this point; it’s more about protecting your invested effort, and that is loss aversion.

Duolingo explains how loss aversion contributes to a user’s reluctance to break a long streak, even on their laziest days. In a way, a streak can turn into a habit when loss aversion settles in.

The Fogg Behaviour Model (B = MAP)

Now that we understand the fear of losing the effort invested in longer streaks, another question is: What makes us do the thing in the first place, day after day, even before the streak gets big?

That’s what the Fogg Behaviour Model is about. It is relatively simple. A behaviour (B) only occurs when three factors — Motivation (M), Ability (A), and Prompt (P) — align at the same moment. Thus, the equation B=MAP.

If any of these factors, even one, is missing at that moment, the behaviour won’t happen.

So, for a streak system to be efficient and recurring, all three factors must be present:

Motivation

This is fragile and not something that is consistently present. There are days when you’re pumped to learn Spanish, and days you don’t even feel an iota of willpower to learn the language. Motivation by itself to build a habit is unreliable and a losing battle from day one.

Ability

To compensate for the limitations of motivation, ability is critical. In this context, ability means the ease of action, i.e, the effort is so easy that it’s unrealistic to say it isn’t possible. Most apps intentionally use this. Apple Fitness just needs you to stand for one minute in an hour to earn a tick towards your Stand goal. Duolingo only needs one completed lesson. These tasks do not require all that much effort. The barrier is so low that even on your worst days, you can do it. But the combined effort of an ongoing streak is where the idea of losing that streak kicks in.

Prompt

This is what completes the equation. Humans are naturally forgetful, so yes, ability can get us 90% there. But a prompt reminds us to act. Streaks are persistent by design, so users need to be constantly reminded to act. To see how powerful a prompt can be, Duolingo did an A/B test to see if a little red badge on the app’s icon increased consistent usage. It produced a 6% increase in daily active users. Just a red badge.

Model Limitations

All this being said, there is a limitation to the Fogg model whereby critics and modern research have noticed that a design that relies too heavily on prompts, like aggressive notifications, risks creating mental fatigue. Constant notifications and overtime could cause users to churn. So, watch out for that.

The Zeigarnik Effect

How do you feel when you leave a task of project half-done? That irritates many people because unfinished tasks occupy more mental space than the things we complete. When something is done and gone, we tend to forget it. When something is left undone, it tends to weigh on our minds.

This is exactly why digital products use artificial progress indicators, like Upwork’s profile completion bar, to let a user know that their profile is only “60% complete”. It nudges the user to finish what they started.

Let’s look at another example. You have five tasks in a to-do list app, and at the end of the day, you only check four of them as completed. Many of us will feel unaccomplished because of that one unfinished task. That, right there, is the Zeigarnik effect.

The Zeigarnik effecthe was demonstrated by psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik, who described that we tend to keep incomplete tasks active in our memory longer than completed tasks.

A streak pattern naturally taps into this in UX design. Let’s say you are on day 63 of a learning streak. At that point, you’re in an ongoing pattern of unfinished business. Your brain would rarely forget about it as it sits in the back of your mind. At this point, your brain becomes the one sending you notifications.

When you put these psychological forces together, you begin to truly understand why streaks aren’t just a regular app feature; they are capable of reshaping human behaviour.

But somewhere along the line — I can’t say exactly when, as it differs for everyone — things reach a point where a streak shifts from “fun” to something you feel you can’t afford to lose. You don’t want 58 days of effort to go to waste, do you? That is what makes a streak system effective. If done right, streaks help users build astounding habits that accomplish a goal. It could be reading daily or hitting the gym consistently.

These repeated actions (sometimes small) compound over time and become evident in our daily lives. But there are two sides to every coin.

The Thin Line Between Habit And Compulsion

If you have been following along, you can already tell there’s a dark side to streak systems. Habit formation is about consistency with a repeated goal. Compulsion, however, is the consistency of working on a goal that is no longer needed but held onto out of fear or pressure. It is a razor-thin line.

You brush your teeth every morning without thinking; it is automatic and instinctive, with a clear goal of having good breath. That’s a streak that forms a good habit. An ethical streak system gives users space to breathe. If, for some reason, you don’t brush in the morning, you can brush at noon. Imperfection is allowed without fear of losing a long effort.

Compulsion takes the opposite route, whereby a streak makes you anxious, you feel guilty or even exhausted, and sometimes, it feels like you haven’t accomplished anything, despite all your work. You act not because you want to, but because you’re subconsciously terrified of seeing your progress reset to zero.

Someone even described this perfectly, “I felt that I was cheating, but simply did not care. I am nothing without my streak”. This shows the extreme hold streaks can have on an individual. To the extent that users begin to tie their self-worth to an arbitrary metric rather than the original goal or reason they started the streak in the first place. The streak becomes who they are, not just what they do.

A well-designed ethical streak system should feel like encouragement to the user, not pressure or obligation. This relates to the balance of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation (external rewards, avoiding punishment) might get users started, but intrinsic motivation (doing the task for a personal goal like learning Spanish because you genuinely want to communicate with a loved one) is stronger for long-term engagement.

A good system should gravitate towards intrinsic motivation with careful use of extrinsic elements, i.e., remind users of how far they have come, not threaten them with what they might lose. Again, it is a fine line.

A simple test when designing a streak system is to actually take some time and think whether your products make money by selling solutions to anxiety that your product created. If yes, there’s a high chance you are exploiting users.

So the next question becomes, If I choose to use streak, how do I design it in a way that genuinely helps users achieve their goals?

The UX of Good Streak System Design

I believe this is where most projects either nail an effective streak system or completely mess it up. Let’s go through some UX principles of a good streak design.

Keep It Effortless

You’ve probably heard this before, maybe from books like Atomic Habits, but it’s worth mentioning that one of the easiest ways habits can be formed is by making the action tiny and easy. This is similar to the ability factor we discussed from the Fogg Behaviour Model.

“

If a daily action requires willpower to complete, that action won’t make it past five days. Why? You can’t be motivated five days in a row.

Case in point: If you run a meditation app, you don’t need to make users go through a 20-minute session just to maintain the streak. Try a single minute, maybe even something as small as thirty seconds, instead.

As the saying goes, little drops of water make the mighty ocean. Small efforts compile into big achievements with time. That should be the goal: remove friction, especially when the moment might be difficult. When users are stressed or overwhelmed, let them know that simply showing up, even for a few seconds, counts as effort.

Provide Clear Visual Feedback

Humans are visual by nature. Most times, we need to see something to believe; there’s this need to visualize things to understand them better and put things into perspective.

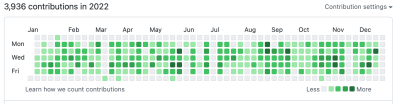

This is why streak patterns often use visual elements, like graphs, checkmarks, progress rings, and grids, to visualize effort. Look at GitHub’s contribution graph. It is a simple visualization of consistency. Yet developers breathe it in like oxygen.

The key is not to make a streak system feel abstract. It should feel real and earned. For instance, Duolingo and Apple’s Fitness activity rings use clean animation designs on completion of a streak, and GitHub shows historical data of a user’s consistency over time.

Use Good Timing

I mentioned earlierthat humans are generally forgetful by nature, and that prompts can help maintain forward momentum. Without prompts, most new users forget to keep going. Life can get busy, motivation disappears, and things happen. Even long-time users benefit from prompts, though most times, they are already locked inside the habit loop. Nevertheless, even the most committed person can accidentally miss a day.

Your streak system most definitely needs reminders. The most-used prompt reminders are push notifications. Timing really matters when working with push notifications. The type of app matters, too. Sending a notification at 9 a.m. saying “You haven’t practiced today” is just weird for a learning app because many have things to do in the day before they even think about completing a lesson. If we’re talking about a fitness app, though, it is reasonable and maybe even expected to be reminded earlier in the day.

Push notifications vary significantly by app category. Fitness apps, for instance, see higher engagement with early morning notifications (7–8 AM), while productivity apps might perform better in early noon. The key is to A/B test your app’s timing based on your users’ behaviours rather than assuming things are one-size-fits-all. What works for a meditation app might not work for a coding tracker.

Other prompt methods are red dots on the app icon and even app widgets. Studies vary, but the average person unlocks their device between 50-150 times a day (PDF). If a user sees a red dot on an app or a widget that indicates a current streak every time they unlock their phone, it increases commitment.

Just don’t overdo it; the prompt should serve as a reminder, not a nag.

Celebrate Milestones

A streak system should try to celebrate milestones to reignite emotions, especially for users deep into a streak.

When a user hits Day 7, Day 30, Day 50, Day 100, Day 365, you should make a big deal out of it. Acknowledge achievements — especially for long-time users.

As we saw earlier, Duolingo figured this out and implemented an animated graphic that celebrates milestones with confetti. Some platforms even give substantial bonus rewards that validate users’ efforts. And this can be beneficial to apps, such that users tend to share their milestones publicly on social media.

Another benefit is the anticipation that comes before reaching milestones. It isn’t just keeping the streak alive endlessly; users have something to look forward to.

Use Grace Mechanisms

Life is unpredictable. People get distracted. Any good streak system should expect imperfection. One of the biggest psychological threats to a streak system is the hard reset to zero after just a single missed day.

An “ethical” streak system should provide the user with some slack. Let’s say you have a 90-day chess learning streak. You have been consistent for three good months, and one day, your phone dies while traveling, and just like that, 90 becomes 0 — everything, all that effort, is erased, and progress vanishes. The user might be completely devastated. The thought of rebuilding it from scratch is so demoralizing that the effort isn’t worth it. At worst, a user might abandon the app after feeling like a failure.

Consider adding a “grace” mechanism to your streak system:

- Streak Freeze

Allow users to intentionally miss a day without penalties. - Extra Time

Allow a few hours (2–3) past the usual deadline before triggering a reset. - Decay Models

Instead of a hard reset, the streak decreases by a small amount, e.g., 10 days is deducted from the streak per missed day.

Use An Encouraging Tone

Let’s compare two messages shown to users when a streak breaks:

- “You lost your 42-day streak. Start over.”

- “You showed up for 42 days straight. That’s incredible progress! Wanna give it another try?”

Both convey the same information, but the emotional impact is different. The first message would most likely make a user feel demoralized and cause them to quit. The second message celebrates what has already been achieved and gently encourages the user to try again.

Streak Systems Design Challenges

Before we go into the technical specifics of building a streak system, you should be aware of the challenges that you might face. Things can get complicated, as you might expect.

Handling Timezones

There is a reason why handling time and date is among the most difficult concepts developers deal with. There’s formatting, internationalization, and much more to consider.

Let me ask you this: What counts as a day?

We know the world runs on different time zones, and as if that is not enough, some regions have Daylight Saving Time (DST) that happens twice a year. Where do you even begin handling these edge cases? What counts as the “start” of tomorrow?

Some developers try to avoid this by using one central timezone, like UTC. For some users, this would yield correct results, but for some, it could be off by an hour, two hours, or more. This inconsistency ruins the user experience. Users care less how you handle the time behind the scenes; all they expect is that if they perform a streak action at 11:40 p.m., then it should register at that exact time, in their context. You should define “one day” based on the user’s local timezone, not the server time.

Sure, you can take the easy route and reset streaks globally for all users at midnight UTC, but you are very much creating unfairness. Someone in California always has eight extra hours to complete their task than someone living in London. That’s an unjust design flaw that punishes certain users because of their location. And what if that person in London is only visiting, completes a task, then returns to another timezone?

One effective solution to all these is to ask users to explicitly set their timezone during onboarding (preferably after first authentication). It’s a good idea to include a subtle note that providing timezone information is only used for the app to accurately track progress, rather than being used as personally identifiable data. And it’s another good idea to make that a changeable setting.

I suggest that anyone avoid directly handling timezone logic in an app. Use tried-and-true date libraries, like Moment.js or pytz (Python), etc. There’s no need to reinvent the wheel for something as complex as this.

Missed Days And Edge Cases

Another challenge you should worry about is uncontrollable edge cases like users oversleeping, server downtime, lag, network failures, and so on. Using the idea of grace mechanisms, like the ones we discussed earlier, can help.

A grace window of two hours might help both user and developer, in the sense that users are not rigidly punished for uncontrollable life circumstances. For developers, grace windows are helpful in those uncontrollable moments when the server goes down in the middle of the night.

Above all, never trust the client. Always validate on the server-side. The server should be the single source of truth.

Cheating Prevention

Again, I cannot stress this enough: Make sure to validate everything server-side. Users are humans, and humans might cheat if given the opportunity. It is unavoidable.

You might try:

- Storing all actions with UTC timestamps.

The client can send their local time, but the server can immediately convert that to UTC and validate against the server time. That way, if the client’s timestamp is suspiciously far, the system can reject it as an error, and the UI can respond accordingly. - Using event-based tracking.

In other words, store a record of each action with metadata including information like the user’s ID, the type of action performed, and the timestamp and timezone. This helps with validation.

Building A Streak System Engine

This isn’t a code tutorial, so I will avoid dumping a bunch of code on you. I’ll keep this practical and describe how things generally operate a streak system engine as far as architecture, flow, and reliability.

Core Architecture

As I’ve said several times, make the serverthe single source of truth for streak data. The architecture can go something like this on the server:

- Store each user’s data in a database.

- Store the current streak store (default as 0) as an integer.

- Store the timezone preference, i.e., IANA Timezone string (either implicitly from local timestamp or explicitly by asking user to select their timezone). For example, “America/New_York”.

- Handle all logic to determine if the streak continues or breaks, with a timezone check that is relative to the user’s local timezone.

Meanwhile, on the client-side:

- Display the current streak, normally fetched from the server.

- Send action done in the form of metadata to the server to validate whether the user actually completed a qualifying streak action.

- Provide visual feedback based on the server responses.

So, in short, the brain is on the server, and the client is for display purposes and submitting events. This saves you a lot of failures and edge cases, plus makes updates and fixes easier.

The Logical Flow

Let’s simulate a walkthrough of how a minimal efficient streak system engine would go when a user completes an action:

- The user completes a qualifying streak action.

- The client sends an event to the server as metadata. This could be “User X completed action Y at timestamp Z”.

- The server receives this event and does basic validation. Is this a real user? Are they authenticated? Is the action valid? Is the timezone consistent?

- If this passes, the server retrieves the user’s streak data from the database.

- Then, convert the received action timestamp to the user’s local timezone.

- Let the server compare the calendar dates (not timestamps) in the user’s local timezone:

- If it is the same day, then the action is redundant and there is no change in the streak.

- If it is the next day, then the streak extends and increments by 1.

- If there is a gap of more than one day, the streak breaks. However, this is where you might apply grace mechanics.

- If the grace mechanism is missed, then reset the streak to 1.

- If you choose to save historical data for milestone achievements, then update variables like “longest streak” or “total active days”.

- The server then updates the database and responds to the client. Something like this:

{ "current_streak": 48, "longest_streak": 50, "total_active_days": 120, "streak_extended": true, } As a further measure, the server should either retry or reject and notify the client when anything fails during the process.

Building For Resilience

As mentioned before, users losing a streak due to bugs or server downtime is terrible UX, and users don’t expect to take the fall for it. Thus, your streak system should have safeguards for those scenarios.

If the server is down for maintenance (or whatever reason), consider allowing a temporary window of additional hours to get it fixed so actions can be submitted late and still count. You can also choose to notify users, especially if the situation is capable of affecting an ongoing streak.

Note: Establish an admin backdoor where data can be manually restored. Bugs are inevitable, and some users would call your app out or reach out to support that their streak broke for a reason they could not control. You should be able to manually restore the streaks if, after investigation, the user is right.

Conclusion

One thing remains clear: Streaks are really powerful because of how human psychology works on a fundamental level.

The best streak system out there is the one that users don’t think about consciously. It has become a routine of immediate results or visible progress, like brushing teeth, which becomes a regular habit.

And I’m just gonna say it: Not all products need a streak system. Should you really force consistency just because you want daily active users? The answer may very well be “no”.

Converting Plain Text To Encoded HTML With Vanilla JavaScript

What do you do when you need to convert plain text into formatted HTML? Perhaps you reach for Markdown or manually write in the element tags yourself. Or maybe you have one or two of the dozens of onl

Javascript

Converting Plain Text To Encoded HTML With Vanilla JavaScript

Alexis Kypridemos

When copying text from a website to your device’s clipboard, there’s a good chance that you will get the formatted HTML when pasting it. Some apps and operating systems have a “Paste Special” feature that will strip those tags out for you to maintain the current style, but what do you do if that’s unavailable?

Same goes for converting plain text into formatted HTML. One of the closest ways we can convert plain text into HTML is writing in Markdown as an abstraction. You may have seen examples of this in many comment forms in articles just like this one. Write the comment in Markdown and it is parsed as HTML.

Even better would be no abstraction at all! You may have also seen (and used) a number of online tools that take plainly written text and convert it into formatted HTML. The UI makes the conversion and previews the formatted result in real time.

Providing a way for users to author basic web content — like comments — without knowing even the first thing about HTML, is a novel pursuit as it lowers barriers to communicating and collaborating on the web. Saying it helps “democratize” the web may be heavy-handed, but it doesn’t conflict with that vision!

We can build a tool like this ourselves. I’m all for using existing resources where possible, but I’m also for demonstrating how these things work and maybe learning something new in the process.

Defining The Scope

There are plenty of assumptions and considerations that could go into a plain-text-to-HTML converter. For example, should we assume that the first line of text entered into the tool is a title that needs corresponding <h1> tags? Is each new line truly a paragraph, and how does linking content fit into this?

Again, the idea is that a user should be able to write without knowing Markdown or HTML syntax. This is a big constraint, and there are far too many HTML elements we might encounter, so it’s worth knowing the context in which the content is being used. For example, if this is a tool for writing blog posts, then we can limit the scope of which elements are supported based on those that are commonly used in long-form content: <h1>, <p>, <a>, and <img>. In other words, it will be possible to include top-level headings, body text, linked text, and images. There will be no support for bulleted or ordered lists, tables, or any other elements for this particular tool.

The front-end implementation will rely on vanilla HTML, CSS, and JavaScript to establish a small form with a simple layout and functionality that converts the text to HTML. There is a server-side aspect to this if you plan on deploying it to a production environment, but our focus is purely on the front end.

Looking At Existing Solutions

There are existing ways to accomplish this. For example, some libraries offer a WYSIWYG editor. Import a library like TinyMCE with a single <script> and you’re good to go. WYSIWYG editors are powerful and support all kinds of formatting, even applying CSS classes to content for styling.

But TinyMCE isn’t the most efficient package at about 500 KB minified. That’s not a criticism as much as an indication of how much functionality it covers. We want something more “barebones” than that for our simple purpose. Searching GitHub surfaces more possibilities. The solutions, however, seem to fall into one of two categories:

- The input accepts plain text, but the generated HTML only supports the HTML

<h1>and<p>tags. - The input converts plain text into formatted HTML, but by ”plain text,” the tool seems to mean “Markdown” (or a variety of it) instead. The txt2html Perl module (from 1994!) would fall under this category.

Even if a perfect solution for what we want was already out there, I’d still want to pick apart the concept of converting text to HTML to understand how it works and hopefully learn something new in the process. So, let’s proceed with our own homespun solution.

Setting Up The HTML

We’ll start with the HTML structure for the input and output. For the input element, we’re probably best off using a <textarea>. For the output element and related styling, choices abound. The following is merely one example with some very basic CSS to place the input <textarea> on the left and an output <div> on the right:

See the Pen [Base Form Styles [forked]](https://codepen.io/smashingmag/pen/OJGoNOX) by Geoff Graham.

You can further develop the CSS, but that isn’t the focus of this article. There is no question that the design can be prettier than what I am providing here!

Capture The Plain Text Input

We’ll set an onkeyup event handler on the <textarea> to call a JavaScript function called convert() that does what it says: convert the plain text into HTML. The conversion function should accept one parameter, a string, for the user’s plain text input entered into the <textarea> element:

<textarea onkeyup='convert(this.value);'></textarea>onkeyup is a better choice than onkeydown in this case, as onkeyup will call the conversion function after the user completes each keystroke, as opposed to before it happens. This way, the output, which is refreshed with each keystroke, always includes the latest typed character. If the conversion is triggered with an onkeydown handler, the output will exclude the most recent character the user typed. This can be frustrating when, for example, the user has finished typing a sentence but cannot yet see the final punctuation mark, say a period (.), in the output until typing another character first. This creates the impression of a typo, glitch, or lag when there is none.

In JavaScript, the convert() function has the following responsibilities:

- Encode the input in HTML.

- Process the input line-by-line and wrap each individual line in either a

<h1>or<p>HTML tag, whichever is most appropriate. - Process the output of the transformations as a single string, wrap URLs in HTML

<a>tags, and replace image file names with<img>elements.

And from there, we display the output. We can create separate functions for each responsibility. Let’s name them accordingly:

html_encode()convert_text_to_HTML()convert_images_and_links_to_HTML()

Each function accepts one parameter, a string, and returns a string.

Encoding The Input Into HTML

Use the html_encode() function to HTML encode/sanitize the input. HTML encoding refers to the process of escaping or replacing certain characters in a string input to prevent users from inserting their own HTML into the output. At a minimum, we should replace the following characters:

<with<>with>&with&'with'"with"

JavaScript does not provide a built-in way to HTML encode input as other languages do. For example, PHP has htmlspecialchars(), htmlentities(), and strip_tags() functions. That said, it is relatively easy to write our own function that does this, which is what we’ll use the html_encode() function for that we defined earlier:

function html_encode(input) { const textArea = document.createElement("textarea"); textArea.innerText = input; return textArea.innerHTML.split("<br>").join("\n"); } HTML encoding of the input is a critical security consideration. It prevents unwanted scripts or other HTML manipulations from getting injected into our work. Granted, front-end input sanitization and validation are both merely deterrents because bad actors can bypass them. But we may as well make them work a little harder.

As long as we are on the topic of securing our work, make sure to HTML-encode the input on the back end, where the user cannot interfere. At the same time, take care not to encode the input more than once. Encoding text that is already HTML-encoded will break the output functionality. The best approach for back-end storage is for the front end to pass the raw, unencoded input to the back end, then ask the back-end to HTML-encode the input before inserting it into a database.

That said, this only accounts for sanitizing and storing the input on the back end. We still have to display the encoded HTML output on the front end. There are at least two approaches to consider:

- Convert the input to HTML after HTML-encoding it and before it is inserted into a database.

This is efficient, as the input only needs to be converted once. However, this is also an inflexible approach, as updating the HTML becomes difficult if the output requirements happen to change in the future. - Store only the HTML-encoded input text in the database and dynamically convert it to HTML before displaying the output for each content request.

This is less efficient, as the conversion will occur on each request. However, it is also more flexible since it’s possible to update how the input text is converted to HTML if requirements change.

Applying Semantic HTML Tags

Let’s use the convert_text_to_HTML() function we defined earlier to wrap each line in their respective HTML tags, which are going to be either <h1> or <p>. To determine which tag to use, we will split the text input on the newline character (\n) so that the text is processed as an array of lines rather than a single string, allowing us to evaluate them individually.

function convert_text_to_HTML(txt) { // Output variable let out = ''; // Split text at the newline character into an array const txt_array = txt.split("\n"); // Get the number of lines in the array const txt_array_length = txt_array.length; // Variable to keep track of the (non-blank) line number let non_blank_line_count = 0; for (let i = 0; i < txt_array_length; i++) { // Get the current line const line = txt_array[i]; // Continue if a line contains no text characters if (line === ''){ continue; } non_blank_line_count++; // If a line is the first line that contains text if (non_blank_line_count === 1){ // ...wrap the line of text in a Heading 1 tag out += `<h1>${line}</h1>`; // ...otherwise, wrap the line of text in a Paragraph tag. } else { out += `<p>${line}</p>`; } } return out; } In short, this little snippet loops through the array of split text lines and ignores lines that do not contain any text characters. From there, we can evaluate whether a line is the first one in the series. If it is, we slap a <h1> tag on it; otherwise, we mark it up in a <p> tag.

This logic could be used to account for other types of elements that you may want to include in the output. For example, perhaps the second line is assumed to be a byline that names the author and links up to an archive of all author posts.

Tagging URLs And Images With Regular Expressions

Next, we’re going to create our convert_images_and_links_to_HTML() function to encode URLs and images as HTML elements. It’s a good chunk of code, so I’ll drop it in and we’ll immediately start picking it apart together to explain how it all works.

function convert_images_and_links_to_HTML(string){ let urls_unique = []; let images_unique = []; const urls = string.match(/https*:\/\/[^\s<),]+[^\s<),.]/gmi) ?? []; const imgs = string.match(/[^"'>\s]+\.(jpg|jpeg|gif|png|webp)/gmi) ?? []; const urls_length = urls.length; const images_length = imgs.length; for (let i = 0; i < urls_length; i++){ const url = urls[i]; if (!urls_unique.includes(url)){ urls_unique.push(url); } } for (let i = 0; i < images_length; i++){ const img = imgs[i]; if (!images_unique.includes(img)){ images_unique.push(img); } } const urls_unique_length = urls_unique.length; const images_unique_length = images_unique.length; for (let i = 0; i < urls_unique_length; i++){ const url = urls_unique[i]; if (images_unique_length === 0 || !images_unique.includes(url)){ const a_tag = `<a href="${url}" target="_blank">${url}</a>`; string = string.replace(url, a_tag); } } for (let i = 0; i < images_unique_length; i++){ const img = images_unique[i]; const img_tag = `<img src="${img}" alt="">`; const img_link = `<a href="${img}">${img_tag}</a>`; string = string.replace(img, img_link); } return string; } Unlike the convert_text_to_HTML() function, here we use regular expressions to identify the terms that need to be wrapped and/or replaced with <a> or <img> tags. We do this for a couple of reasons:

- The previous

convert_text_to_HTML()function handles text that would be transformed to the HTML block-level elements<h1>and<p>, and, if you want, other block-level elements such as<address>. Block-level elements in the HTML output correspond to discrete lines of text in the input, which you can think of as paragraphs, the text entered between presses of the Enter key. - On the other hand, URLs in the text input are often included in the middle of a sentence rather than on a separate line. Images that occur in the input text are often included on a separate line, but not always. While you could identify text that represents URLs and images by processing the input line-by-line — or even word-by-word, if necessary — it is easier to use regular expressions and process the entire input as a single string rather than by individual lines.